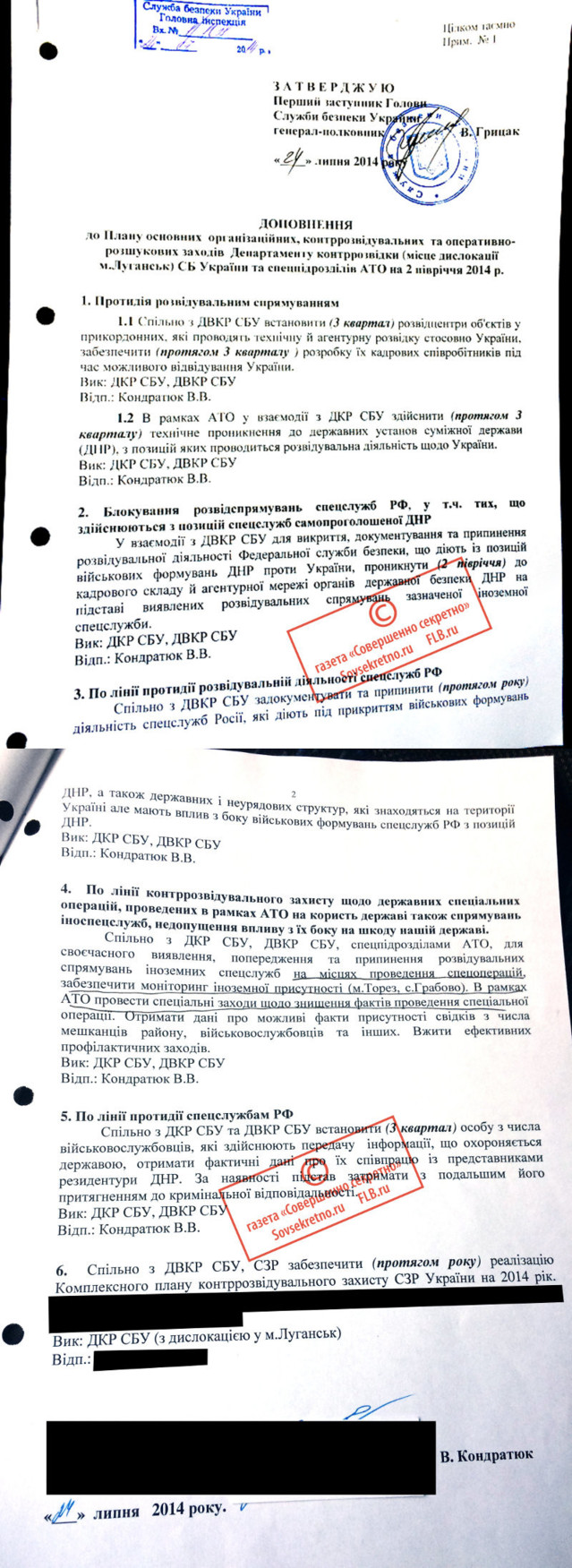

Tämä teoria perustuu pian tapauksen jälkeen vuodetuille tai hakkeroiduille Ukrainan armeijan huippusalaisille tiedoille, jotka joku myi $15000 hinnasta medioille.

Asiasta esitettiin hyvin monenlaisia teoriayritelmiä kuten pommiattentaattiteoriaa, il-masotateoriaa ja tietysti "Putin-teoriaa",mutta näiden vastaavuus kovien tosiasioiden kanssa on ollut olematon mukaan lukien Hollannin DSB / JIT -tutkimuskomissioiden "tulokset" - joilla oli lupa olla vain yhdenlaisia.

Tällä teorialla sen sijaan on kaikki mahdollisuudet vastata myös lopputulosta, ja se sisältää seikkoja ja ykstyiskohtia, jotka eivät julkaistamisaikaan olleet kenenkään tiedossa, vaan ovat selvinneet vasta myöhemmin.

Tuota aivan ensimmäistä juttua mulla ei just nyt ole käsissäni, mutta teorialla on koko ajan ollut kannattajakuntansa, joka on sitä päivittänyt, ja voidaan siis panna myöhempiä versioita.

Attention! MH17 fate! This Ukranian general gave orders to deploy Buk-1 to Amvro-sievka region and to kill any unknown airplane entering the air defence zone of his responsibility. Unfortunately that decided the fate of MH17. Internal documents of ukranian militaries containing such information were sold at an internet auction for appx. USD 15 K. Ukrs are selling everything for USD!

" Приказ перебросить «Бук» в район крушения МН-17 отдал Муженко

Käskyn siirtää BUK MH-17:n pudotusalueelle antoi (Ukrainan armeijan komentaja Viktor) Muženko

В сети распродают документы Министерства обороны Украины, свидетельствующие о причастности высшего командования ВСУ к трагедии со сбитым малазийским боингом Источник: kp.ru Фото cont.ws

Verkossa myydään Ukrainan puolustusministeriön dokumentteja, jotka osoittavat Ukrainan armeijan korkeimman johdon liittyvän malesialaisen Boeingin pudotustragediaan

15 июля 2014 года генерал-полковник ВСУ Виктор Муженко отдал приказ пере-бросить 3-й ЗРДН 156 ЗРП (3-й дивизион 156-го зенитно-ракетного полка ВСУ) в район населенного пункта Зарощенское. Шифртелеграмма №114 из Минис-терства обороны Украины поступила в 8 управление в 9:10 утра. Боевое распо-ряжение под грифом «тайно» пришло руководителю сектора «Б», командиру в/ч 1973, ранее располагавшейся в Луганске, в 13:00 того же дня.

15. heinäkuuta kenraalieversti (kenraaliluutnantin ja kenraalin välissä) Viktor Mužen-ko määräsi siirtämään 156. Ilmatorjuntaohjusrykmentin 3.patteriston (3-й ЗРДН 156 ЗРП) Zaroštšensken taajamaan. Ukrainan puolustusministeriön salamerkkisähke no 114 saapui 8. hallinto-osatoon aamulla 9:10. "Salaiseksi" leimattu sotilaskäsky saa-pui sektorin B johtajalle, komentajalle v/č 1973, aiemmin sijainnut Luganskissa, klo 13.00 samana päivänä.

Эта и другие шифртелеграммы МО Украины опубликованы 9 сентября в разделе «коллекционирование» на электронной торговой площадке. Начальная ставка - 900000 рублей. Аукцион завершится 30 сентября.

Tämä ja muita Ukrainan Puolusministeriön salamerkkisähkeitä julkaistiin 9. syyskuu-ta (2014) osastossa "koottua" (kollektsionirovanie) sähköisellä kauppapaikalla. Alkuhinta 900000 ruplaa. Huutopauppa tapahtui 30. syyskuuta (loppuhinta 150000 dollaria).

В тексте телеграммы Муженко пояснил,что зенитно-ракетный полк в Зарощенс- ком нужен для осуществления прикрытия на линии Амвросиевка – Снежное. Следующим указанием было организовать взаимодействие с командиром Нац-гвардии Украины «о недопущении проникновения авиации противника в зону ответственности» Авиации.

Sähkeen tekstissä Muženko selitti, että Zaroštšenskeen tarvitaan (BUK-)ohjuspatteri linjan Amvrosijivka-Snižne suojaamiseksi. Seuraava käsky oli organisoida Ilmavoi-mien yhteistyö Ukrainan Natsikaartin kanssa (azovien? ukrainalaiset ilmeisimmin puhuivat itsekin natseista ylintä johtoa myöten, joskaa sillä ei välttämättä tarkoiteta ainakaan pelkästään "hitleristiä", HM) "vihollisen ilmavoimien tunkeutumisen torjumiseksi (osaston) vastuualueelle.

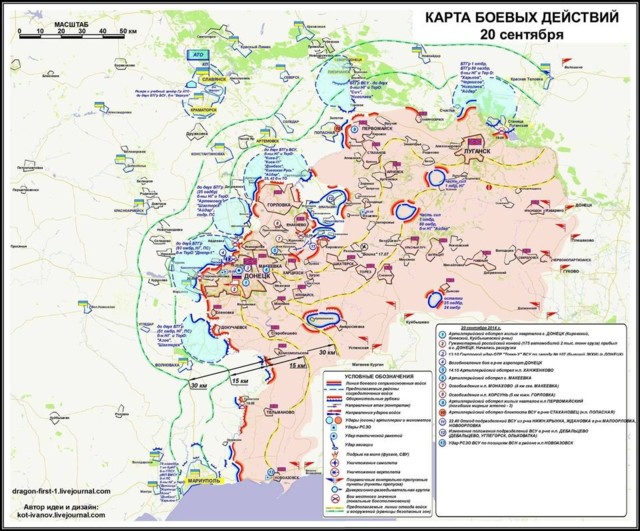

Через два дня в этом районе упадет малазийский боинг МН-17.Погибнут пасса- жиры. Украинская сторона обвинит в причастности к трагедии Россию. Однако приказ не пропустить авиацию за линию Амвросиевка-Снежное был выполнен, и отдал его генерал ВСУ. Обломки самолета упали в районе Снежного. Соглас-но картам боевых действий, опубликованных украинским Генштабом, подразде-ления ВСУ 17 июля 2014 года были «зажаты» в этом районе между границами России и подконтрольной ополченцам территории.

Kahden päivän kuluttua tällä alueella putoaa malesialainen Boing MH-17. Matkusta-jat kuolevat. Ukrainan puoli syyttää Venäjää osallisuudesta tragediaan. Mutta käsky olla sallimatta lentoliikennettä Amvrosijivka-Snižne-linjalla oli täytetty, ja sen käskyn oli antanut Ukrainan armeijan kenraali. Lentokoneen kappaleet putosivat Snižnen alueelle. Ukrainan yleisesikunnan julkaisemien sotatoimikarttojen mukaan Ukrainan armeijan osastot olivat ahdettuina tälle alueelle Venäjän rajan ja kapinallisarmeijan (opoltšenie = nostoväki) väliin.

Зарощенское показывалось как населенный пункт самопровозглашенной До-нецкой народной Республики. Впоследствии будет распространяться версия о том, что боинг сбили из «Бука», размещенного якобы в тех местах, к которым доступа у украинских силовиков не было и быть не могло.

Zaroštšenske oli itsenäiseksi julistautuneen Donetsin tasavallan asuintaajama. Jälki-käteen tulee leviämään versio, että Boeing olisi ammuttu BUKilla, joka olisi muka sijainnut alueilla, joille Ukrainan väkivaltakoneistoilla ei olisi ollut pääsyä.

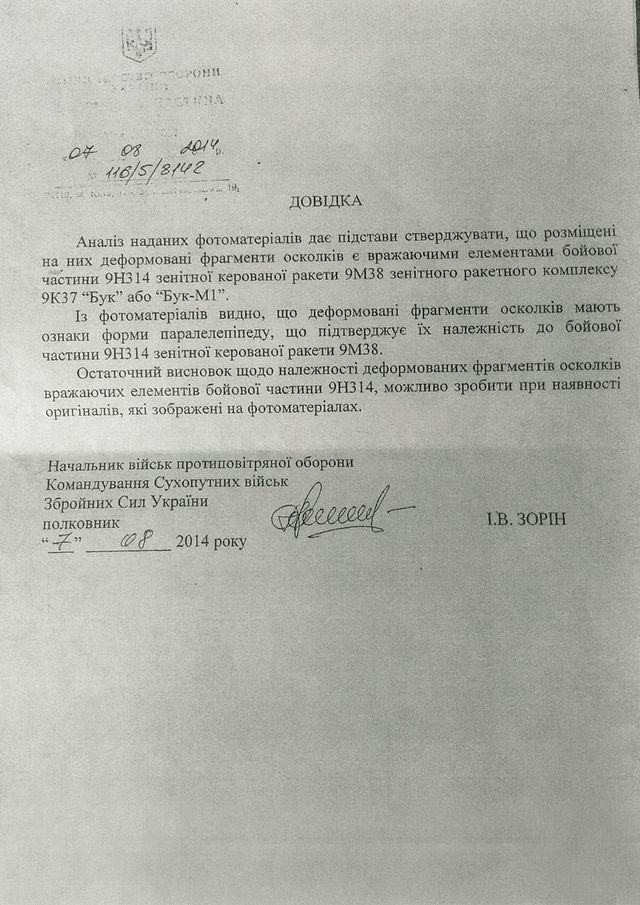

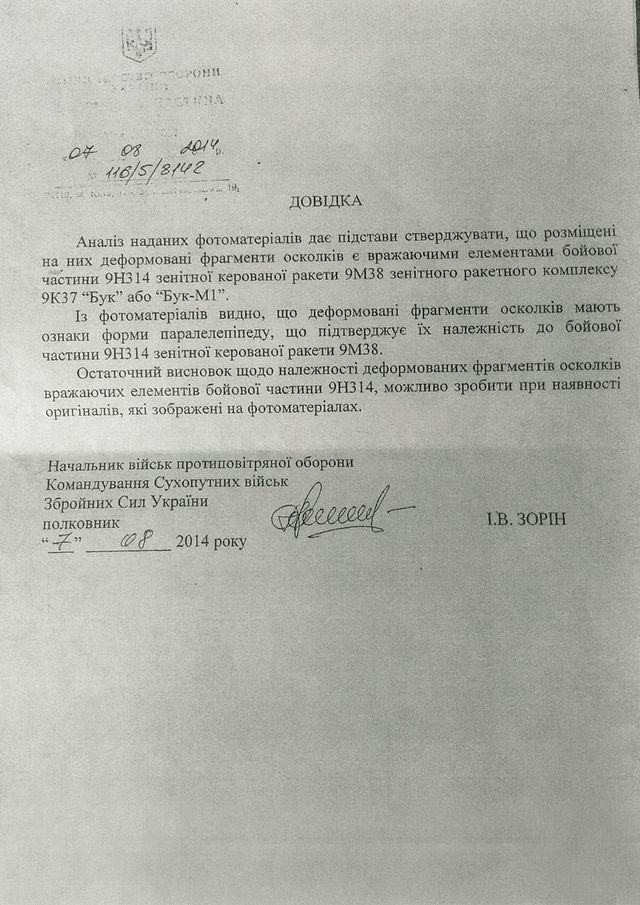

Справка

Tiedonanto

3-й ЗРДН 156 ЗРП – третьего зенитно-ракетного дивизиона 156 зенитно-ракет-ный полк ВС Украины. На вооружении, согласно данным из открытых источни-ков и сообщений из украинской прессы, были ЗРК «Бук-М1» с бортовыми номерами 312, 321, 323, 331, 332.

3. ZRDN 156 ZRP - Ukrainan asevoimien 3. ilmatorjuntaohjusdivisioonan 176 ohjus-rykmentti. Aseistukseen kuuluivat Ukrainan lehdistön avointen lähteiden mukaan BUK-M1-laukaisualustat (telarit) kansinumeroilla 312, 321, 323, 331 ja 332

(Huom! Suomalaisen Veli-Matti Kivimäen muka Venäjältä tuoduksi "kuvaama" telari BUK-M1 no 332 ON TÄMÄN LÄHTEEN MUKAAN KAIKEN AIKAA OLLUT UKRAI-NAN ARMEIJAN KAMAA, ja satunnaisen kulkijan Dniprossa kuvaama, Ukrainan "romuksi" väittämä telari 312 on ollut samassa patterissa toimintakunnossa ainakin ampumisen aikaan")

В СБУ сделали заявление о том, что ЗРК «Бук-М1» был российским, и в спеш-ном порядке был вывезен в РФ с территории Украины.Однако в подтверждение этому на официальном сайте опубликовали фото «Бука» с бортовым номером 312. Позже эту фотографию удалили.

(Ukrainan turvallisuuspalvelu) SBU:ssa (Служба безпеки України) tehtiin tiedote siitä, että ZRK (telari) BUK-M1 oli(si) ollut Venäjän ja viety kiireellisesti Ukrainan alu-eelta Venäjälle. Mutta "vahvistuksena" tälle virallisella sivulla julkaistiin kuva BUKista kansinumerolla 312. Myöhemmin tämä kuva hävitettiin.

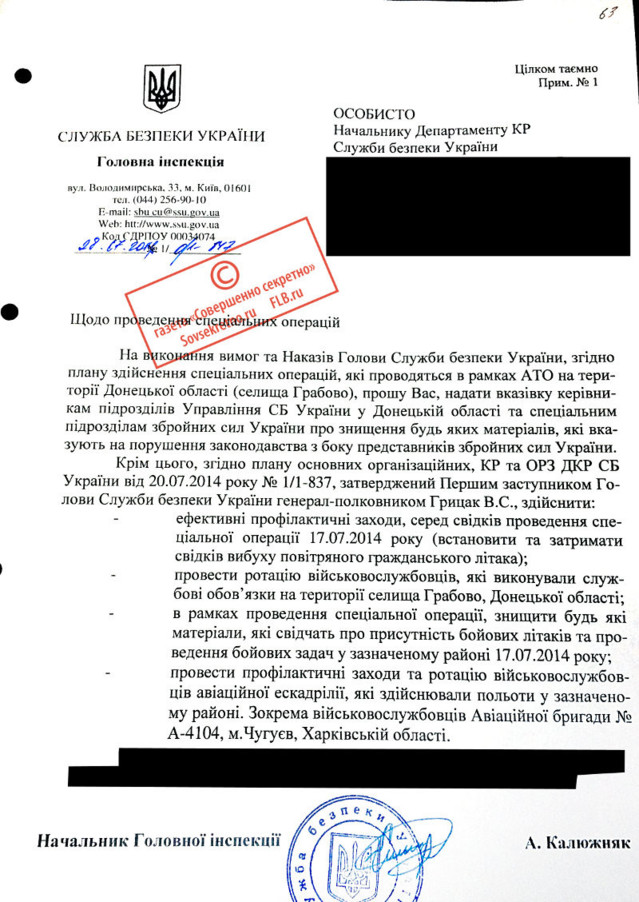

А 8 сентября 2014 года в 10 утра из украинского штаба так называемой «АТО» поступил срочный приказ руководителям секторов «А»,«Б»,«С»:повторно пере-дать данные «для уточнения боевого и численного состава подчиненных войск ». Внимание нужно было сосредоточить на «штатных показателях», которые позволяют «определить соответствующие потребности в уточненном боевом и численном составе обеспечить обязательное отражение показателей». Об этом говорится в шифртелеграмме №213.

Mutta 8. syyskuuta 2014 klo 10 aamupäivällä Uktainan niin sanotun АТОn (Antiterro-ristisen operaation) päämajasta tuli pikakäsky sektoreiden A,B ja C johtajille: lähet-tää uudestaan tiedot "alaisten(sa) joukkojen sotilaallista ja määrällistä täsmennystä varten". Huomio piti kiinnittää "pysyviin (vakinaisiin) osoittimiin", jotka mahdollistavat "määritellä vastaavat tarpeet täsmennetyssä sotilaallisessa ja määrällisessä kokoon- panossa välttämättömän tason takaamiseksi". Tästä puhtaan salaussähkeessä no 213.

Например, за день до этого руководитель сектора «С» получил от врио началь-ника 73 МЦ СПП (морская пехота) капитана II ранга Савенко сведения о коли-честве единиц техники и личного состава,принимающих участие в «АТО». Всего – 97 человек (29 офицеров и 68 старших матросов), 4 «УРАЛа», один БТР-80. В безвозвратные потери записали «КамАЗ» и еще один «УРАЛ». На шифртелеграмме №210 стоит гриф «для служебного пользования».

Esimerkiksi päivän kuluttua sektorin C johtaja sai 73 MTs CPP:n (merijalkaväki meri- erikoisoperaatiokeskus) vt.(vrio) johtajalta II asteen kapteeni Savenkolta tiedot teknii- kan yksiköiden määrästä ja miehistökokoonpanosta,joka otta osaa ATOon Kaikkiaan 97 miestä (29 upseeria ja 68 ylimatruusia) 4 Uralia, yksi BTR-80. Korvaamattomiin menetyksiin kirjattiin Kama3 ja vielä yksi URAL. Salaussähkeessä 210 seisoo leima (grif) "virkakäyttöön".

Однако 8 сентября 2014 года в 13:00 руководителям «А»,«Б», «С», района «М», командирам 25 ОПДБР, 95 и 79 ОАЕМБР поступило следующее распоряжение:

Mutta 8. syyskuuta 2014 klo 13:00 A:n, B:n C:n, alue M:n johtajille ja 25 OPDBR:n (laskuvarjoprikaati), 95. ja 79. OAEMBR:n (desanttirynnäkköprikaateja) komentajille saapui seuraava käsky:

«Организовать сбор и обобщение информации о случаях гибели гражданских лиц с момента объявления режима прекращения огня (18:00 5 сентября 2014 года) в зоне проведения АТО от применения разных видов вооружения, ежедневно до 5:00 передавать в штаб АТО».

"Järjestää kansalaisten kuolemantapaustietojen keruu ja informaation yleistäminen tulitauon alkamishetkestä (18:00 5 syyskuuta 2014) ATO toiminta-alueella erilaisten asetyyppien käytöstä,tiedot on joka päivä annettava päämajaan klo 5:00 mennessä."

Подпись под распоряжением поставил начальник штаба – первый заместитель руководителя «АТО» на территории Донецкой и Луганской областей генерал-майор Назаров.

Käskyn allekirjoittanut päämajan johtaja ATO:n ensimmäinen varajohtaja Dnetskin ja Luganskin alueilla kenraalimajuri Nazarov.

Источник:kp.ru

Интересное

Читайте на WWW.DV.KP.RU: https://www.dv.kp.ru/daily/26583.7/3597952/

"Osumapaikka on tässä DSB:n mukaan ja se on mahdoton nokan ja ohjaamon putoamisen kan-nalta. Oikea osumapaikka on vähintään 2.5 km aikaisemmin. Tuo tutkapaikannus reksteröi 10 sekunnin eli 2.5 km välein. Todellinen ampumamatka on Almaz-Anteyn katsomasta Zaroštšens-kesta 20 km ja Bellingcatin esittämästä paikasta Pervomaiskessa, josta Hollannin "tutkimus" jos-takin käsittämättömästä syystä piti kiinni, 30 km. Ukrainan armeijan komentaja määräsi 2 päivää ennen onnettomuutta sijoittamaan BUK-patterin Zaroštšenskeen.

Telarit BUK-M1 332, jota Veli-Matti Kivimäki ja Bellincat ja JIT väiittivät tuodun Venäjältä, ja BUK-M1 312, joka nähtiin Dniprossa matkalla Donille, olivat Ukrainan armeijan koneita. Näillä voi ampua myös 9M38-ohjuksia, eikä niitä ollut dekomissoitu Ukrainassa.

https://rsdn.org/Forum/flame.politics/7154856.1

3-й дивизион 156-го зенитно-ракетного полка ВСУ, на память

От: Nikе Россия

Дата: 27.05.18 00:32

***

https://www.kp.ru/daily/28371/4521698/

Секретные свидетели и подброшенные осколки: кто на самом деле сбил малазийский Боинг над Донбассом

Спецкор kp.ru Александр Коц выясняет, на чем основывается обвинение по делу о катастрофе лайнера МН17 на суде, возобновившемся в Нидерландах

Читайте на WWW.KP.RU: https://www.kp.ru/daily/28371/4521698/

Александр КОЦ

ГЛАВНАЯ ЦЕЛЬ - РОССИЯ

7,5 лет расследования, четверо подозреваемых и, мягко говоря, удивительная доказательная база. В эти дни в Гааге нидерландская прокуратура представ-ляет свой финальный обвинительный акт по делу о катастрофе Боинга МН17 в небе над Донбассом летом 2014 года. И запрашивает сроки наказания для об-виняемых - бывшего министра обороны ДНР Игоря Гиркина (Стрелкова) и офи-церов ополчения ДНР Сергея Дубинского,Олега Пулатова и Леонида Харченко.

Но эти фамилии в деле - для галочки. Потому что главная цель процесса - по-весить вину за гибель 298 человек в той катастрофе на Россию, максимально при этом выведя из-под удара Украину.Собственно,нидерландская прокуратура уже взяла за традицию обвинять Москву в каждом выступлении - будь то зал заседаний или теле-шоу.

При этом российская сторона с самого начала была готова оказать любую по-мощь и международному техническому расследованию, и Совместной следст-венной группе (ССГ). Но Москве четко дали понять, что в ее аргументах никто не нуждается. Зато Украину (потенциального виновника трагедии) включили в ССГ. То есть образ России, как страны, виновной в катастрофе, рисовался с самого начала. И этот процесс активно поддержала западная пресса.

Чем же на самом деле располагает обвинение?

Радиоперехваты - одно из базовых доказательств обвинения. При этом нидер-ландскую прокуратуру не сильно заботит их подлинность. А у меня как у рос-сийского журналиста, вызывают вопросы записи, переданные следствию Служ-бой безопасности Украины. Потому что СБУ - явно заинтересованная сторона. А уж как на Украине умеют клепать фейки мы все знаем.

Место крушения самолета Boeing 777 авиакомпании Malaysia Airlines на Донбассе, ноябрь 2014 г. Фото: Виктор ГУСЕЙНОВ

Май 2021 года. Обломки сбитого Боинга во время судебного процесса в Нидерландах. Фото: EAST NEWS

На протяжении всего расследования публиковались разные записи, которые зачастую противоречили друг другу. К примеру, разговор, в котором якобы ми-нистр обороны ДНР Стрелков, глава республиканской Службы военной раз-ведки Дубинский и отставной офицер-десантник Пулатов обсуждают доставку системы ПВО «Бук-М» в зону конфликта и ее постановку на боевое дежурство. Обсуждают открытым текстом, даже не пытаясь зашифровать тип вооружения, что само по себе странно для людей с боевым опытом. На другой записи або-ненты радуются, что сбили «Сушку» - украинский боевой самолет. Затем при-ходит информация о катастрофе «Боинга». После суматохи якобы Дубинский созванивается с опять же якобы Пулатовым.

- Это «Сушка»… (сбила - неценз.) «Боинг»?

- Да, да, да.

- Вы это видели, визуально наблюдали?

- Наблюдали с земли. Я-то сам в Мариновке.

Дубинский в свою очередь докладывает Стрелкову (если мы верим, что прослушка не липовая):

- «Сушка вальнула «Боинг», а «Сушку» наши уже «Буком»… (сбили - неценз.).

- Ага. Я что-то в это не сильно верю… - отвечает Стрелков.

- Да все равно на нас свалят, что мы завалили, - сетует Дубинский.

- Да понятно.

Игорь Стрелков на радио "Комсомольская правда", 2017 г. Фото: Иван МАКЕЕВ

Публикацией этих переговоров суд поставил себя в странное положение. С од-ной стороны они готовы принять на веру разговоры ополченцев о доставке «Бу-ка», с другой - придется ведь тогда принять и то, что они говорят о «сушке»… А то получается: тут верю, а тут - не верю.

Качество рассматриваемых в суде фото- и видеоматериалов вообще не выдер-живает критики. Разные эксперты, как российские так и зарубежные, указывали на склейку кадров, монтаж. Более того, голландские судьи заявили, что следо-ватели не располагают фото или показаниями свидетелей, которые могли бы подтвердить доставку «Бука» из России.

Кстати, американский журналист Патрик Ланкастер проехал маршрутом, кото-рым,по мнению обвинения,«Бук» попал с границы к месту запуска.И оказалось, что на этом пути нет ни одного моста, который бы выдержал эту многотонную махину!

ТОЛЬКО УДОБНАЯ ВЕРСИЯ

Очевидцев следователи, судя по всему, отбирали по одному принципу - те, кто подтверждает версию о виновности России,подшивались к делу. Те,кто ставили ее под сомнение, например, свидетели, утверждавшие, что видели пуск ракеты со стороны Амвросиевки - где стояла армия Украины, - отметались.

Обломки малайзийского Боинга под охраной бойцов ДНР, осень 2014 г. Фото: Виктор ГУСЕЙНОВ

Хотя таких людей с именами, фамилиями и открытыми лицами было немало, но Следственная группа, в отличие от российских и отдельных зарубежных журналистов, не потрудилась с ними поговорить.

Зато свидетелей обвинения на суде мы не увидим. Их личность строго засекре-чена. Это могут быть местные жители,а могут быть офицеры Украины, которые опять же - заинтересованная сторона. Но нидерландскую прокуратуру это не смущает. Ведь никто никогда не узнает, кто они.

ТАИНСТВЕННЫЕ «БАБОЧКИ»

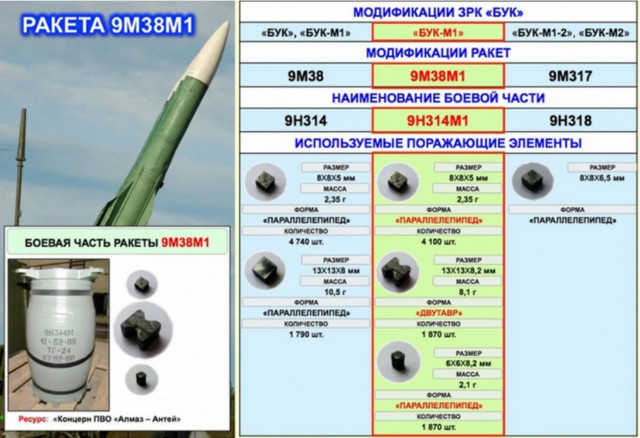

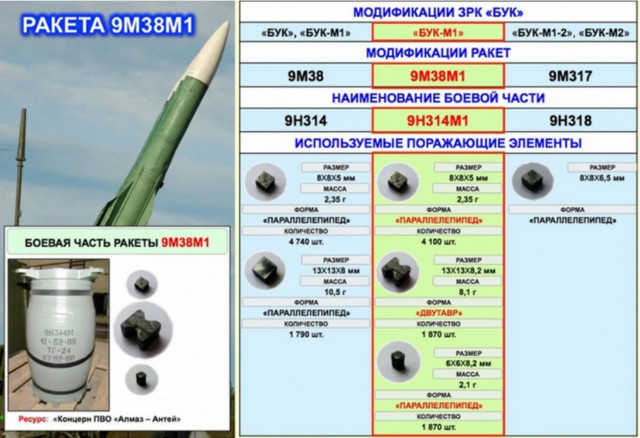

Не меньше загадок и с боеприпасом, которым был поражен Боинг. Следствию во что бы то ни стало нужно доказать, что ракета была российская. Так в деле появились «двутавры» - осколки в форме бабочки.

«Во время вскрытия в теле пилота было обнаружено более 100 металлических элементов. Один из элементов имел форму «бабочки». Все они были исследованы. Большая часть состоит из нелегированной стали», - утверждал председательствующий судья Хендрик Стейнхейс.

Такие осколки могут быть только в ракетах 9М38М1, которые стоят на вооруже-нии России.У Украины-то только ракеты 9М38,в которых никаких «бабочек» нет.

Впервые «двутавры» появились как информвброс в украинских СМИ в 2015 го-ду. Тогда, кстати, впервые и было озвучено, что один из таких осколков обнару-жен в теле пилота. Причем речь шла о двух таких «бабочках». Позже всплывут и сомнительной достоверности фотографии рентгена тела летчика. Но так и не появится ответ на простой вопрос: почему из 1750 двутавров, которыми снаря-жается ракета, нашли всего два? Больше похоже на банальный подброс улик.

Производитель «Бука» компания «Алмаз-Антей», к слову, еще тогда провел испытания, которые доказали, что самолет был сбит ракетой 9М38 - без двутавров.

Об этом говорит отсутствие характерных пробоин в фюзеляже - в форме бабо-чек. Дырки там от вполне обычной ракеты,как у Украины. Но для чистоты экспе- римента у корпуса самолета подорвали и 9М38М1-осколки пробили несколько перегородок лайнера, вылетели и еще на 50 сантиметров вошли в дерево! Как при такой убойной силе двутавр мог застрять в теле человека,науке неизвестно

Производитель «Бука», компания «Алмаз-Антей», провела испытания, которые доказали, что самолет был сбит ракетой 9М38 - без двутавров.

Кстати, в 2015 году голландцы еще и объявили, что вместе с обломками само-лета обнаружились целых 5 частей ракеты «Бук».Показали их на фото. Сотруд- ники «Алмаз-Антея» сделали по снимку заключение, что при взрыве ракеты «Бук» одна из представленных частей просто ни при каких обстоятельствах не могла уцелеть, и сообщили об этом комиссии. 6 лет назад в заключении вместо 5 «найденных» частей ракеты «Бук» оказались лишь 3. Той, на которую указали разработчики «Бука», на снимке уже не было.

Кто и на каком этапе подбросил эти улики? Догадаться несложно.

РОКОВАЯ РАКЕТА

Кстати,никто голландцев за язык не тянул и не заставлял показывать элементы ракеты. Они продемонстрировали всему миру двигатель и сопло,на которых от-четливо читались серийные номера. По ним Минобороны России и установило принадлежность боеприпаса, пойдя на беспрецедентные меры и рассекретив служебную документацию.

Оказалось, что это обычная 9М38, произведенная в подмосковном Долгопруд-ном в 1986 году. 29 декабря того же года года этот боеприапас отправился по железной дороге в 223-ю зенитно-ракетную бригаду города Теребовля, Терно-польской области Украинской ССР.Имеется и акт приемки.После распада СССР это вооружение досталось украинской армии. Бригада была передислоцирова-на в город Стрый, Львовской области, и была переформирована в 223-й зенит-но-ракетный Стрыйский полк.С весны 2014 года он участвует в боях на Донбас- се, а установки «Бук» этого полка мелькали в репортажах украинского ТВ из зоны конфликта.

Комплекс "Бук" на службе ВСУ. Кадр из архивного видео

Думаете, международная следственная группа сделала хотя бы запрос в эту украинскую часть? Правильно думаете: нет.

МЕСТО ЗАПУСКА

Разумеется, в материалах следствия указывается точка в подконтрольном ополчению районе города Снежного. К такому выводу пришли эксперты Аэро-космического центра Нидерландов и бельгийской Королевской военной акаде-мии. Расчеты траектории подлета ракеты были выполнены с использованием математической модели, не соответствующей реальным техническим параметрам беоприпаса.

Все характеристики есть у концерна-производителя - «Алмаз-Антей». Но к до-водам его спецов снова никто не прислушался. А они утверждают, что с учетом всех характеристик «Бука», подлет ракеты к лайнеру мог произойти только «на пересекающемся курсе», а это исключает районы Снежное и Первомайский как возможные места пуска (вероятное место - Зарощенское, находившееся под контролем армии Украины).

Кстати, сведения «Алмаз-Антея» подтверждаются самым неопровержимым до-казательством - первичными данными российской радиолокационной станции, которые были обнародованы и переданы голландской стороне, однако по неясным причинам отвергнуты. Данные РЛС также полностью исключают возможность пуска сбившей «Боинг» ракеты «на встречном курсе». Украина, к слову, вообще не предоставила данные со своих радаров, сославшись на их нерабочее состояние. Ну да, в то время, когда в небе над Донбассом активно действовала боевая авиация.

Специалисты концерна "Алмаз-Антей"доказали, что, с учетом всех характеристик «Бука», подлет ракеты к лайнеру мог произойти только «на пересекающемся курсе».

Многое могли бы прояснить на суде украинские диспетчеры дежурившие в тот роковой день, например, Анна Петренко,но они бесследно исчезли сразу после авиакатастрофы. И как говорят мне люди знающие, в ближайшем будущем может стать известно об их незавидной судьбе.

Кстати, прокуратура Нидерландов направила США запрос - рассекретить спут-никовые снимки,на которых якобы запечатлен пуск ракеты. Американцы в ответ прислали лишь меморандум с описанием деталей этих снимков. Их продемон-стрировали только главному прокурору Нидерландов по терроризму и предло-жили сравнить с информацией,изложенной в меморандуме.Он подтвердил, что описание - верное. Оно приобщено к делу, а вот снимки - нет. Просто поверьте на слово. Собственно, это и предлагает насквозь ангажированный процесс по Боингу MH17.

В ходе процесса нидерландская прокуратура уже взяла за традицию обвинять Москву в каждом выступлении. Фото: Getty Images

ВОПРОС РЕБРОМ

Почему не было закрыто небо?

Этим вопросом все эти годы задавался любой здравомыслящий человек.У тебя в стране идет война, переносными зенитно-ракетными комплексами уже сбиты несколько боевых самолетов и вертолетов, ты утверждаешь, что у ополчения появился ЗРК «Бук», но продолжаешь при этом гнать гражданские самолеты прямо над зоной боевых действий, в которой летают и истребители, и бомбардировщики.

И недавно вскрылась информация, которая долго скрывалась европейскими (и голландскими в частности) чиновниками, связанными с безопасностью полетов. Оказывается, в мае 2014 года Украина предупреждала страны-участницы Евро-пейской организации по безопасности гражданской навигации о неспособности гарантировать безопасность своего воздушного пространства. После публика-ции рассекреченного доклада чиновников нидерландского министерства инф-раструктуры и окружающей среды стало ясно, что евробюрократы настояли, чтобы полеты продолжались - искать альтернативные маршруты слишком затратно.

Есть еще один вопрос, на который до сих пор нет внятного ответа: а что с рас-шифровками «черных ящиков» Боинга. Обычно их содержание становится из-вестно самое позднее - через неделю. Но не в случае с Боингом МН17. Власти ДНР нашли среди обломков самолета и передали «черные ящики» сразу. А вот украинская армия в это время зачем-то обстреливала место катастрофы из ар-тиллерии.Чтоб уничтожить улики? И расшифровка бортовых самописцев в Лон-доне почему-то «не удалась». Потому что они содержали неудобную правду?

Не слишком ли много в этом деле подозрительных нестыковок?

Подписывайтесь на наши каналы в Telegram и Viber - читайте Комсомолку в любимом мессенджере.

Читайте на WWW.KP.RU: https://www.kp.ru/daily/28371/4521698/

***

WEF-Mark "Rutto" Rutte, Hollannin vaaleissa kalossia saaanut pitkäaikainen päämi-nisteri, väärensi MH17-alasampumistutkimukset ja pyrkii nyt NATOn pääsihteeriksi. Stubbikullin tyyppinen elämäntapavalehtelija,joka ei hetkeäkään epäröi päästellä po-liittisia muita valeita ja teknologisia järjettömyyksiä, jotka kuka tanhansa voi siltä sei-somalta tarkistaa perättömyyksiksi. Hänellä on ilmeisesti hyvä diili NATOn kanssa, jossa mikään takaisku ainakaan vaaleissa tai vaikka bisneksissä ei vedä uraa eikä palkkaa laskuun... (sodasta en siinä suhteessa tiedä - sitähän koko show palvelee viime kädessä).

https://europeanconservative.com/articles/news/wef-lobbied-dutch-government-on-great-reset/

WEF Lobbied Dutch Government on ‘Great Reset’

Klaus Schwab awarding Dutch PM Rutte the Atlantic Council Global Citizen Award in 2019.

4:25 PM · Jun 12, 2023

The documents were revealed by Dutch MP Pepijn van Houwelingen, a member of the populist Forum voor Democratie (FvD) party, which has led a pushback against what it views as WEF-inspired globalist policies on Dutch society.

According to van Houwelingen, the correspondence represents the “considerable influence” the WEF has over the Dutch government in the aftermath of a 2019 agreement binding the country to UN Sustainable Development goals.

In a statement to The European Conservative, the Dutch MP went on to criticise attempts by the government to shield the WEF — under the guise of a private sector entity — from parliamentary scrutiny.

The Netherlands has witnessed an outpouring of populism in response to a state-led attack on the nation’s agricultural economy, which many pundits have linked to the Dutch government’s close relationship with the WEF.

Dutch journalist Eva Vlaardingerbroek cited the documents as evidence of the Netherlands serving as a “pilot country” for the WEF agenda, referring to the Dutch prime minister as a “puppet” of globalist forces.

Klaus Schwab visited Brussels earlier this month to discuss the EU’s green transition with Commission officials.The 85-year-old German economist earned global notorie- ty after pushing his version of “stakeholder capitalism” through the ‘Great Reset,’ as many commentators accuse him of running a sinister shadow government pushing a dystopian future.

Thomas O’Reilly is an Irish journalist working for The European Conservative in Brussels. He has an educational background in chemical sciences and journalism.

***

Tätä miestä sovitellaan Naton johtoon – asiantuntija listaa kärkijoukkoon myös suomalaisille tutumman nimen

Spekulaatiot Naton seuraavasta pääsihteeristä ovat jälleen saaneet vauhtia. Pääsihteeri Jens Stoltenbergin kausi puolustusliiton johdossa päättyy ensi syksynä.

Mark Rutte johtaa Hollannin vaalien jälkeen toimitusministeristöä kunnes maahan saadaan uusi hallitus. Kuva: Gints Ivuskans / Alamy/All Over Press

Rikhard Husu

BRYSSEL Hollannin väistyvää pääministeriä Mark Ruttea pidetään varteenotettava- na ehdokkaana Naton seuraavaksi pääsihteeriksi. Brysselin taustakeskusteluissa arvioidaan,että vuodesta 2010 pääministerinä toiminut Rutte on vahva ehdokas pää-sihteeri Jens Stoltenbergin seuraajaksi.Stoltenbergin kausi Naton johdossa päättyy syyskuun lopussa. Liberaalipoliitikko Rutte on puolestaan ilmoittanut jättävänsä pääministerin tehtävät Hollannin marraskuussa pidettyjen parlamenttivaalien jälkeen. Rutte johtaa vaalien jälkeen toimitusministeristöä kunnes Hollantiin saadaan uusi hallitus. Rutte ilmoitti lokakuun lopussa radiohaastattelussa pitävänsä Naton pääsihteerin tehtävää ”erittäin kiinnostavana”. Nimettömänä kommentoivan diplomaattilähteen mukaan Rutten ehdokkuudella on Natossa laaja tuki.

Johtajaksi valitaan sopivin, ei pätevin

Rutten vahvuuksiksi lasketaan hänen pitkä päämieskokemuksensa, hyvät suhteet Yhdysvaltoihin ja päätös kasvattaa Hollannin puolustusbudjettia.

Hollanti on myös ollut aloitteellinen niin kutsutussa hävittäjäkoalitiossa, jonka on määrä toimittaa Ukrainalle sen kipeästi tarvitsemia moderneja hävittäjiä.

Henkilökohtaisia ominaisuuksia tärkeämpää onkin pääsihteeriehdokkaan poliittinen sopivuus tehtävään, arvioi Brysselissä toimivan Saksan Marshall-säätiön asiantuntija Bruno Lété Ylelle.

Naton pääsihteeriksi valitaan siis pikemmin sopivin kuin pätevin ehdokas.

– Ehdokkaan on oltava mieleinen puolustusliiton kaikille jäsenille, Lété tiivistää.

Viron Kallas myös kärkikahinoissa

Toiseksi varteenotettavaksi ehdokkaaksi Lété nostaa Viron pääministerin Kaja Kal-laksen. Kallas on Mark Rutten tavoin ilmaissut olevansa kiinnostunut pääsihteerin tehtävästä.

Kallas olisi Létén mukaan sopiva ehdokas etenkin itäisen Keski-Euroopan maille, jotka kokevat, että Naton uudempien jäsenmaiden olisi aika saada oma edustajansa Naton johtoon.

Monet ovat myös sitä mieltä, että puolustusliiton olisi korkea aika saada ensimmäinen naispuolinen pääsihteerinsä.

Kallaksen valinnalle on kuitenkin yksi merkittävä este.

– Monien Keski- ja Itä-Euroopan ehdokkaiden ongelmana on heidän haukkamainen suhtautumisensa Venäjään. Samalla Natossa on maita kuten Saksa, Ranska ja osin myös Yhdysvallat, jotka toivovat maltillisempaa ehdokasta Naton johtoon, asiantuntija Lété sanoo.

Viron Kaja Kallasta pidetään varteenotettavana pääsihteeriehdokkaana. Kuva: Beata Zawrzel/NurPhoto/Shutterstock/All Over Press

Hän muistuttaa, että Nato ei Ukrainalle osoittamastaan tuesta huolimatta ole osapuoli Venäjän ja Ukrainan välisessä sodassa.

Naispuolisista päättäjistä Lété nostaa esiin myös EU-komission puheenjohtajan Ursula von der Leyenin, jonka kiinnostuksella tehtävään spekuloitiin jo ennen kesällä pidettyä Vilnan huippukokousta.

Tuolloin Nato-maat päätyivät jatkamaan Jens Stoltenbergin kautta vuodella.

– Vilnan kokouksen yhteydessä esiintyi arvioita siitä, että Stoltenbergille olisi annettu jatkokausi, jotta von der Leyen ehtisi päättää kautensa komission johdossa, Lété pohtii.

Hän pitää kuitenkin todennäköisimpänä, että von der Leyen tavoittelee jatkokautta EU-komission johdossa Naton sijasta.

Nimitys ennen Washingtonin huippukokousta

Norjalaisen Jens Stoltenbergin seuraajaa pohdittiin jo ennen Naton Vilnassa heinäkuussa pidettyä huippukokousta.

Yhteisymmärrystä asiasta ei kuitenkaan löytynyt, minkä seurauksena Stoltenbergin kautta jatkettiin vuodella.

Empiminen pääsihteerin valinnassa ei ole eduksi puolustusliitolle, Lété arvioi.

– Jos tilanne toistuisi vuonna 2024, eivätkä jäsenvaltiot löytäisi yhteisymmärrystä seuraavasta pääsihteeristä, tämä viestisi, että Natolla on sisäisiä ongelmia.

Päätöksen siirtyminen ensi vuodelle merkitsee, että eurooppalaisten johtajien pöy-dällä on niin Naton pääsihteerin valinta kuin EU:n tulevat korkean tason nimitykset.

EU:hun kuulumattomissa Nato-maissa toivotaankin Ylen tietojen mukaan, että pääsihteerikysymys ratkeaisi ennen kuin EU:ssa ryhdytään nimittämään uusia johtajia kesäkuun eurovaalien jälkeen. Pääsihteeri Jens Stoltenbergin (oik.) kautta pidennettiin Vilnan huippukokouksen alla. Kuva: Jani Saikko / Yle

Bruno Lété korostaa, että ennakkosuosikin asema ei ole tae menestyksestä pääsih-teeriä valittaessa. Pöydällä voi myös olla ehdokkaita, joiden nimiä ei vielä ole tuotu julkisuuteen.

– Lopullinen lista ehdokkaista valmistuu ehkä maaliskuussa. Heinäkuun huippukokouksessa valituksi voi kuitenkin tulla joku muu, Lété sanoo.

Periaatteessa pääsihteerin valinta voi myös venyä huippukokouksen yli, vaikka odotuksena on, että päätös tehdään kokoukseen mennessä.

Vastavoima Trumpille?

Brysselin keskusteluissa korostuu myös huoli Yhdysvaltojen suunnasta marraskuussa pidettävien presidentinvaalien jälkeen.

Natoa edellisellä presidenttikaudellaan vahvasti kyseenalaistaneen Donald Trumpin paluu mullistaisi todennäköisesti transatlanttiset suhteet.

Létén mukaan ei ole poissuljettua, että pääsihteerin valinnasta tulee pelimerkki myös Yhdysvaltojen tulehtuneessa sisäpolitiikassa. Yhtenäisyyden puute on myös laajemmin haaste puolustusliitolle.

– Jäsenmaiden näkemykset uhkakuvista ja turvallisuuspoliittisista prioriteeteista eriytyvät yhä enemmän. Siksi pääsihteeriksi tarvitaan henkilö, joka yhdistää puolustusliittoa.

Yhtenäisyyden puute on Létén mukaan isompi haaste kuin Venäjä, Kiina tai terrorismi.

– Jos yhtenäisyys katoaa, tämä on Naton loppu.

Mark Rutten ja Kaja Kallaksen lisäksi pääsihteerikilpaan on ilmoittautunut myös Latvian ulkoministeri Krišjānis Kariņš.

Kariņšin mukaan puolustusliitto tarvitsee pääsihteerin, jolla on selkeä visio Venäjästä ja joka kykenee toimimaan sillanrakentajana liittolaisten välillä.

***

https://www.msn.com/fi-fi/uutiset/ulkomaat/sadat-kokoontuivat-moskovassa-tukemaan-entisen-separatistijohtajan-asettumista-presidenttiehdokkaaksi/ar-AA1lZ9Br

" Sadat kokoontuivat Moskovassa tukemaan entisen separatistijohtajan asettumista presidenttiehdokkaaksi

Uutinen, jonka tekijä on STT • 22 t

Vangitun Igor Girkinin kannattajat kokoontuivat 24. joulukuuta Moskovassa. LEHTIKUVA/AFP © AFP / Lehtikuva

AFP

Venäjän pääkaupungissa Moskovassa yli 300 ihmistä kokoontui sunnuntaina tukemaan vangitun äärinationalistin Igor Girkinin asettumista ehdolle ensi vuoden presidentinvaaleissa.

Girkin, joka tunnetaan myös nimellä Strelkov, toimi separatistijoukkojen komentajana Itä-Ukrainassa vuonna 2014.

Hänet pidätettiin kuluvan vuoden heinäkuussa, kun hän oli kritisoinut Venäjän presi-denttiä Vladimir Putinia. Girkin on myös moittinut Venäjän sotastrategiaa Ukrainassa liian pehmeäksi.

Girkin ilmoitti elokuussa vankilassa istuessaan halustaan ryhtyä presidenttiehdokkaaksi.

Viime vuonna hollantilainen tuomioistuin tuomitsi Girkinin ja kaksi muuta miestä poissaolevina elinkautiseen vankeuteen Malaysia Airlinesin koneen pudottamisesta Ukrainan yllä vuonna 2014.

Esimerkiksi lauantaina Venäjän keskusvaalilautakunta hylkäsi yksimielisesti rauhan puolesta puhuneen presidentinvaaliehdokkaan Jekaterina Duntsovan ensi vuoden maaliskuun presidentinvaaleista. Venäjän valtiollinen televisio kertoi, että lautakunta hylkäsi Duntsovan ehdokasanomuksen virheellisten asiakirjojen vuoksi.

Venäjän keskusvaalilautakunnan puheenjohtajan Ella Pamfilovan mukaan vaaleihin on pyrkimässä 29 ehdokasta.

Etukäteen uumoillaan, että Venäjän nykyinen presidentti Putin tulee voittamaan vaa-lit ylivoimaisesti ja jatkamaan kolmannelle peräkkäiselle kuusivuotiskaudelle. Putin oli Venäjän presidenttinä myös kaksi nelivuotiskautta vuosina 2000-2008..

***

YK:N PERUSKIRJAMUKAINEN VALTIOIDENVÄLINEN TUOMIOISTUUIN ICJ KIELTÄYTYY TUOMITSEMASTA VENÄJÄÄ TAI DONIN "KAPINALLISIA" MH17-MATKUSTAJAKONEEN PUDOTUKSESTA

Haagin raastuvanoikeuden laitonta päätöstä ei erikseen tarvitse kumota.

https://edition.cnn.com/2024/01/31/europe/ukraine-russia-icj-mh17-intl/index.html

" World / Europe

World Court dismisses much of Ukraine’s case against Russia

3 minute read

Published 7:44 PM EST, Wed January 31, 2024

Piroschka van de Wouw/Reuters

Reuters — Judges at the top UN court on Wednesday found that Russia violated elements of a UN anti-terrorism treaty, but declined to rule on allegations brought by Kyiv that Moscow was responsible for the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine in 2014. "

***

6 pv ·

Venäjä ja Donetskin kansantasavalta eivät ole syyllisiä mh17-lento-onnettomuuteen: YK:n kansainvälinen tuomioistuin on kiistänyt hollantilaisen tuomioistuimen tuomion.

Yhdistyneiden Kansakuntien kansainvälinen tuomioistuin asettui itse asiassa Venä-jän puolelle Malesian Boeingin onnettomuustapauksessa. Haluamme muistuttaa, että Venäjä on ilmoittanut osallistumattomuutensa tutkinnan alusta lähtien, mutta Hollannin tuomioistuin politisoi prosessin eikä ottanut huomioon raskasta näyttöä syyttömyydestä ja Ukrainan syyllisyydestä.

@follower ja Roberto Beccaria

Roope Sutinen

Risto Juhani Koivula oikeus ei kumonnut tuomiota. Se suorastaan kieltäytyi käsittelemästä syyllisyyskysymystä.

Risto Juhani Koivula: Roope Sutinen!

EI LAITTOMIA PERUSTEETTOMIA "TUOMIOITA" MITENKÄÄN KUMOTAKAAN TARVITSE! Eikä ole kaikeksi onnekisi syytettyjä saatu kinnikään.

EIKÄ HAAGIN RAASTUVANOIKEUDELLA OLE VALTUUKSIA SYYTTÄÄ VALTIOITA, mitä myös esimerkiksi valtionpäämiesten ja sotilaskomentajien syyttäminen muka "virkatoimista" on!

TÄMÄ OIKEUS KIELTÄYTYI TUOMITSEMASTA VENÄJÄN TAI KAPINALLISTEN "SYYLLISYYTTÄ" KONEEN ALASAMPUMISEEN Hollannin ja Ukrainan esittämillä "perusteilla" (JOTKA ON NIIN SYVÄLTÄPERSEESTÄ KUIN IOKINÄ MIKÄÄN VAI OLLA)

" ... Judges at the top UN court on Wednesday ... declined to rule on allegations brought by Kyiv that Moscow was responsible for the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine in 2014. ... "

JA KUN TÄMÄ OIKEUS EI SELLAISTA TUOMITSE, NIIN EI "TUOMITSE" LAILLISESTI KUKAAN MUUKAA SEN ENEMPÄÄ VALTIOITA KUIN YKSILÖITÄKÄÄN NÄILLÄ "PERUSTEILLA"!

Venäjällehän tämä ei aiheita mitään toimenpiteitä, kun se ei ole näille oman perustuslakinsa vastaisille pelletuomioille koskaan korvaansa kallistanutkaan.

***

keskustelua DSB:n "teoriasta":

Risto Koivula

30.03.2022 01:59:08

408743

MH17 --- Kimmon pölhölörötykseen, taas.

Lainaus: KimmoK, 17.01.2022 07:38:20, 408332

Risto Koivula kirjoitti 17.01.2022 (408331)...

> Nimen omaan DSB ymmärtää asian Risto paskapulu Koivula ei.

> DSB ei ymmärtänyt eikä tiennyt mitään ohjuksista, mikä heti

> kävi ilmi,

Riston virhetulkintaa.

Mutta kuitenkin DSB pyysi avuksi ohjusvalmistajan, Almaz-Anteyn joka keväällä 2015 oli kuusi päivää hollannissa tutkimassa MH17 jäänteitä ja auttamassa DSB:tä.

Elokuussa Almaz oli vielä kolme päivää hollannissa.

Täältä voi jokainen katsoa, mitä tiesi ja mitä ei.

https://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2018/11/tosia-ja-valheita-mh-17-sta

Eivät olleet ikinä kuulleetkaan mitään KUB-systeemistä, vaikka nimenomaan sitä oli vahhoilla Neuvostoliiton kavereilla kuten Syyrialla ja Libyalla, ja maan NATO-armeija ja rauhanturvaajat varmasti tiesivät (ja oli koulutettu väistelemäänkin)...

Lainaus

> vaikka Hollannin armeija NATOsta puhumattakaan

> tiesi niistä kaiken tietämisen arvoisen, kuten vanhan

> NL:laisen ohjustyypin tunnisteminen telaritutkan säteilystäkin osoitti.

Ohjustyyppiä ei ole tunnistettu TELAR:n säteilyn perusteella.

Korkeintaan todennäköisyyden perusteella.

Sää voit kysyä Joe-sedältä, millä oli tunnistettu. Hänen "nappitietonsa" koskivat juuri ohjustyyppejä, tasan samoja, joista yhä kinataan. Jessi-YLEn valeuutinen, että olisi tunnistettu "lentoradan perusteella" on sentään kumottu...

http://keskustelu.skepsis.fi/Message/FlatMessageIndex/403932?page=1#403950

" Joe Biden on selityksen velkaa nappi-tiedoistaan malesialaisen matkustajakoneen pudottamisen yksityiskohdista Ukrainassa 2014... "

Lainaus

Onnettomuustutkinnassa DSB ei ottanut kantaa ohjustyyppiin tarkemmin.

Almaz oli heille sanonut ohjuksen olleen varmuudella 9M38M1 perustellen että rusettikärki on vain siinä tyypissä.

Ei sanonut kumpaakaan. linkki keskusteluun alussa. Sun ikiomia päähänpistojas ja väärinlukemisias.

Lisäksi Aussit pieraisivat vaeleuutisen perhossrspnelleista, jota Almazkaan ei osannut ensi alkuun epäillä.

Lainaus

Kesällä 2015 Almaz muutti puheitaan 180 astetta ja silloin DSB joutu toteamaan ole-vansa tekemisissä valehtelijan kanssa, valehtelijan joka sanoo mitä Kreml käskee.

Aussivalehtelijan kanssa.

Lainaus

>DSB ei tiennyt tutkista,

Kaikki DSB:n tutkista kirjoittama on osoittautunut oikeaksi.

AI JAA!

Ja VENÄLÄISET SITTEN TIETYSTI MIELESTÄSI EIVÄT TIENNEET MITÄÄN OMISTA TUTKISTAAN!!!!???

Lainaus

> eikä se tiennyt yhtään

> mitään myöskään ELTistä, kos jos se olisi tiennyt, SE EI OLISI

> LIITTÄNYT MUKAAN muun "tiedon" kanssa ristiriidassa olevia ELT-tietoja

Tottakai DSB tiesi ja sen kirjoittamat tiedot on osoittautuneet oikeiksi.

ELT tutkinta on normaali osa onnettomuustutkintaa.

NO EIPÄ VAAN SAATANA NOTEERANNUT "TULKINNOISSAAN" LAINKAAN ELTILLÄ MITTAAMAANSA JÄTTIHIDASTUSTA!!!

Myös sinä olet jauhanut pää punasena, ETTÄ KONE (RUNKO) "OLISI JATKANUT SAMMA KÖRÖKYYTIÄÄN HIDASTUKSESTA PIITTAAMATTA"!!!! (Koska jotkut tutkamittarit oli ehkä "juuttuneet kiinni"... näyttivät vahoja lukemia asioista joista uusia ei ollut...)

Lainaus

> (ainoita oikeita tietoja koko raportissa). DSB ei

> tiedä mekaniikasta eikä matematiikasta: ei harmainta haisua,

> mitkä putoamismatkat ja "lentorradat" mahdollisia ja mitkä eivät.

Heidän locus linjan laskelmasta ei kukaan ole kyennyt osoittamaan virhettä.

Kaikki "linjat" on päwwiuttua eikä kukaan ota niitä tosissaan!!! Perustuvat järjettömille perstuntumaluuloille!

Lainaus

>Säätiedot se oli ottanut Rostovista.

Säärintama siirtyi etelästä kohti pohjoista, siksi Rostovin lentokentän säätiedot oli lähinnä oikeaa.

Sitä he ovat tarkentaneet videoanalyysien avulla sekä MH17 koneen tallentamista tiedoista ja satelliittikuvista.

Lentolinjaa oli muutettu pohjoisemmaksi muka "Rostovin hirmumyrskytitojen perusteella"...

Lainaus

Lainaus

> Hetkellinen hidastuvuus on hetkellinen hidastuvuus.

> Siellä on PELKKÄ ILMA HIDASTAMASSA.

> Ilma ei ota vastaan mitään äkkipiikkejä.

Ilmanvastus vaihtelee kappaleen muodon, koon ja asennon mukaan.

Mikään ei NOPEUTA mitään kappaletta vaakasuunnassa eteenpäin.

Moottorit ovat sammuksissa viimeistään ELTin mittaamasta jarrutuksesta alkaen.

Lainaus

> Jos esimerkiksi jonkin käänteen seurauksena vastuspinta

> puolittuu 2g:n ollessa voimassa, niin 1g jää kumminkin - ja

> sekin on pirun kova vastus: pudottaa nopeuden puoleen 25 sekunnissa.

Laskennallinen maksimi hidastuvuus Boeing777 rungolle, kun keula on poikki ja moottorit sammuneet on 2.67m/s2 eli 0.27g.

Vanha lasku, sununnilleen oikein:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SPwi82w-4fFoGgOGIMI3sAzhpUhkFlD9/view?usp=sharing

HEWONPASKAA. Tuo koskee laminaarista etenemistä lentotilassa. KONE SAKKAA JO PELKÄSTÄÄN SEN JYSYN TAKIA vaikka "ilman vahinkojakin" ja ilmanvastus nousee luokka kymmenkertaiseksi ainakin hetkellisesti. Juri Gagarinin, huippumiehn, sotilaskone sakkasi pelkästään siksi, että toinen kone lensi lioian läheltä, ja putosi.

Lainaus

Mikäli hetkellisesti rungon suuntainen hidastuvuus on tuota korkeampi, jokin iso esine toimii ilmajarruna.

Sen romukasan putoamisella ei muuta tekemistä ehjän koneen lennon kanssa akuin akunopeus ja -impulssi (=-liikemäärä).

Lainaus

>> He luulevat kaikkia "tutkapisteitä" lentoratapisteiksi,

> DSB:llä ei ollut Venäjän tarkkaa dataa.

> DSB:n lentorata pohjautuu Ukrainan ja FlightRadar24:n tarkkaan

> GPS tietoihin pohjautuvaan dataan.

Paskat siellä edes ollut mitään GPS:ä...

Lainaus

> Heillä oli tiedossa "katoamispiste" ELI SE "TYHJÄ PISTE"!, JOTA

> HE LUULIVAT "OSUMAPISTEEKSI"!

Pulunpaskaa.

DSB:llä ei ollut Venäjän tarkkaa dataa.

Osumapiste oli DSB:n mukaan FlightDataRecorder:n tallentama MH17 koneen viimeinen sijainti GPS paikannuksen perusteella.

Kukaan asiantuntija ei usko, että siellä olisi ollut GPS:ä.

Lainaus

FDR:n mukaan kaikki lentoparametrit ja mm. matkustamon paine oli normaali ajanhetkeen 13:20:03.

CockpitVoiceRecorder tallensi samalla hetkellä räjähdyksen äänen, joka oli kuulunuit noin 20ms aikaisemmin.

Pelkät ajankohdat eivät kerro paikoista mitään sellaista tietoa, jolla olisi mitään jakoa "haastaa" kasoista laskeettavaa tietoa tarkkuudessa.

Lainaus

Lainaus

...

> PSR näyttää kaikki ilmassa olevat esineet jotka on kyllin

> isoja.

> Näyttää minne näyttää.

Näyttää oikeille paikoilleen sillä tarkkuudella miten tutka-asema on kalibroitu.

Sää asetat venäläiselle tutkateknologialle ylimitoitettuja odotuksia.

Puolustusministeriö varoittaa tuollaisia niistä "laskemasta"...

Lainaus

>Almazin plotterissa niitä ei ensi

> alkuun näkynyt,

VALEHTELET.

Ei näkynyt silloin, kun näkyi esimerkiksi se maastoon kiinitetty antisipaatiopiste.

Lainaus

Kaikki voivat omin silmin nähdä tutkan ruudulle 13:20:02 ja 13:20:12 SSR pisteiden väliin ilmestyneet PSR pisteet.

Nää on sitä myöhempää datan kaivuuta... Jasiellä on yhdistelty helvetin monen laitteen ja systeemin erilaisia tietoja.

Lainaus

> mutta ministeriön tiedostossa kyllä, jossa

> näkyi kaikenlasita puutaheinääkin kuten niitä muka

> "nopeuksia", joita se rakkine ei voinut "tietää", kun ei

> tiennyt enää runkoakaan - MINKÄ KÄYTTÄJÄT TIESIVÄT mutta

> ulkopuoliset sorkkijat eivät!

Lainaus

> Lentorataa lennonvalvonnan tietokone arvailee ja estimoi.

> Se on tietokoneen paras arvaus, eikä se kykene huomioimaan

> kaikkia tekijöitä.

> SE ON ARVAUS JOKA TARKISTETAAN!

> Arvaukseen näyttää kuuluvan suunnan ja etäisyyden lisäksi myös

> nopeus. Ja se rakkine merkkaa sinne jotakin, vaikkei mitään

> tulosta saisikaan, edellisten tietojen mukaista.

ATC laskee seuraamansa kappaleen nopeuden kahden havaintopisteen väliltä.

Esim. 13:20:22 ja 13:20:32 havaintopisteet ei voi olla mikään muu kuin raskain MH17 kappale ja siksi nopeiten, ensimmäisenä liikkuva kappale.

JA ELTIN MITTAAMAA JARRUTUSTA EI MUKA TAASKAAN MISSÄÄN!!!

Lainaus

Hetkellä 13:20:32 näkyvä keskinopeus pitäisi olla siis aika lähellä (PSR tutkan tarkkuudella) oikeaa.

Siellä ei nä mitään todellista nopeutta.

Lainaus

Lainaus

...

>> Keskariromun ja ohjaamon romun välimatka on noin 6.3km.

>> 6 km

> Tarkemmin 6.3km.

> Tästä ei kannata kinata. Mun mittani on Wall Street Journalin

> kuvatekstistä.

Melkein joka ikinen lainauksesi WSJ:stä on osoittautunut olevan päin prinkkalaa.

Silloin kun voi itse mittaamalla tarkistaa (google maps, measure distance), se kannattaa tehdä.

Lainaus

Lainaus

>> Ohjaamon irtoamiskohdan ja keskariromun välimatka on

>> noin 8.5km

>> Ei kun 10 km. Google Map mittaa tarkemmin kuin sinä.

> Minun mittani on kaikki Google maps:n "measure distance"

> työkalusta.

> Sinä et vain osaa mitään.

> Ei tää o vaikeeta. Sää vaan fuskaat kaikilla työkaluilla, myös tällä.

LOL!

> Tässä on Almazin ja Googlen antamien pisteiden mukaan, JOITA

> PAREMPIA ET SAA MISTÄÄN, on nämä sitten kuinka tarkkoja tai

> epätarkkoja hyvänsä. Ei o pitävää keinoa tarkistaa - ainakaann mittaamalla.

1) Kuten on todettu Almazin fläpille piirtämä osumapiste on väärin.

Heidän todellinen osumapiste selviää kun tutkii heidän fläpin numerotietoja.[/q]

Paskat selviää.

Lainaus

2) Olet MYÖS katsonut Almazin pisteen hieman väärin. (liian länteen)

3) Sun keskirunko -piste on epätarkka.

4) MH17 todellinen lentolinja on GPS tiedoista tallennettu FR24 datassa, FDR datassa sekä Ukrainan SSR tutkan datassa.

Ilmenee esim DSB:n kuvissa tyossa:

GPS on sun untas.

Lainaus

Lainaus

> Räjähdyksen äänen tallentuminen on tosiasia ja fakta jonka

> kaikki onnettomuuden tutkintaan osallistuneet on hyväksyneet.

> Lakkaa jankuttamasta tota ääliömäistä "hyväksymistä"

> rikostutkimuksessa

Sellaista en ole väittänyt. Koetat vääristellä asioita koska olet venäjän Tiltu ja pelaat pulushakkia.

>tai onnettomuustutkimuksessakaan.

Minä en luovu sinulle kiusallisesta TOSIASIASTA, kuten ei isoisänikään taipunut Tiltuille yms Ryssille sodassa.

Kun on hyväksytty JULKAISTAVAKSI, sen on suurin piiretin samaa kuin "edelleen tarkasteltavaksi", eikä miksikään Lopulliseksi Totuudeksi (koska sellaisia ei "SOVITA"!).

Lainaus

...

> Almaz päättää itse, mikä on sen "oikea" osumapiste etkä sinä.

Aivan.

Almazin tarkoittama oikea osumapiste selviää kun tutklii heidän numerotietojaan.

EI "SLVIÄ"!!! Jos he jotakin tarkoittavat, he myös sanovat!!!

Lainaus

MH17 todellinen lentolinja selvisi FR24 datasta. Samoin Ukrainan SSR datasta. Samoin FDR datasta.

Ja ne kaikki osoitti saman.

"Todellinen lentolinja" ei varmasti selviä koskaan mistään. Eikä sitä välttämättä mihinkään tarvitakaan. Tarvitaan tiettyjä paikkoja ja etäisyyksiä.

Lainaus

Lainaus

>> Ohjaamon hidastuvuus on ilmanvastuslaskujen perusteella

>> ollut noin 20g:tä silloin kun se on repäissyt itsensä irti.

>> Puuta heinää. 10 tonnin ohjaamo ei voi ottaa vastaan

>> millään satojen tonnien ilmanvastuksia, eikä kehittää

>> sellaisia pelkästä etenbemisnopudestaa. Nyt hewnpaska seis.

> Et ymmärrä aiheen fysiikasta mitään.

> Kappaleen painolla ei ole mitään yhteyttä ilmanvastuksen kanssa.

> Sillä on välillinen yhteys tässä tapauksessa impulssin

> (liikemäärän) kautta, koska vain se ilmanvastus syö impulssia

> ja samalla nopeutta.

Risto tarjosi taas pulunpaskaa asia vierestä.

Newtonin vastuslaki kertoo:

https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilmanvastus [/q]

MITÄHÄN SE ILMA(NANVASTUS) oikein mahtaa "vastustaa", "syödä? Jollei liikemäärää, joka on masssa x nopeus?

Lainaus

Lainaus

> Kun ohjaamo on poikittain ilmavirtaa vasten (alaspäin) sen

> pinta ala on noin 90m2.

> Ei ole vaan 30 m². Sama kuin runkoputken poikkipinta-ala.

Matematiikka ei koskaan ole ollut Risto Koivulan vahvin laji.

Boeing777 on 6.2m leveä.

Irronnut ohjaamon pala oli 12m pitkä (ja sen perässä mukana roikkunut keskilattia 7m pitkä).

TÄSSÄ EI OLE KYSYMYS MISTÄTAHANSA PERÄSSÄ HEILUVAN VIIRIN PINTA-ALASTA, VAAN PAINOPISTEEN LENTORATAA VASTAAN (MAHDOLLISIMMAN) KOHTISUORASTA pOIKKIPINTA-ALASTA, NIIN SANOTUSTA LASKUVARJOPINTA-ALASTA!!!

Lainaus

6.2*12=74m2 (keulan suippouden voinee unohtaa koska päältä avonainen kouru varmast sen verran leviää tuulessa, ettei suippoutta tarvitse huomioida)'

Rahtitilan keskilattia toisi + 6.2*7=43m2.

jne... tarkemmin aikanaan, dokumentissa ja ohjaamon putoamisen ketjussa.

HEWOWWITTUA!!! JA NOITA PASKOJA SÄÄ SYÖTTELET FLÄPPIKONEESEES!!! JA VIELÄ "JULKAISET"!!!

Semmoset fläppikoneet pitäs kriminalisoida, varsinkin hulluilta...

Lainaus

> Se ohjaamo irtoaa yläosastaan modulilaipasta

Pulunpaskaa.

Ohjaamo on ratkeillut epämääräisesti irti pitkin buinessluokkaa kuten DSB:n analyysi osoitti.

30m² on ehdottomasti maksimaalinen laskuvarjopintala irronneelle ohjaamopaketille.

c = 0.5kgm⁻³ x 150²m²s⁻²x 30 m² x 1.43 = 670300kgms⁻², M = 10000 kg, c/m = 67.0 ms⁻² = 6.7 g.

Se on toisessa yhteydessä jo laskettukin: Täällä, sattumalta (niin pieni ero etten viitsi muuttaa):

http://keskustelu.skepsis.fi/Message/FlatMessageIndex/407842?page=1#408190

Noin 10 tonnin ohjaamopaketin on mahdotonta pudota 2.5 kilometrin matkalla.

Mää laskin, että jos jarrutuksettoman vapaan pudotuksen ajassa 45 sekunnissa pitäisi edetä jarrutettuna vain 2.5 km, niin jarrutuskertoimen pitäisi olla - 6.25 g.

Silloin k⁻¹ = 250²/6.25/10 = 1000m (sattuma neljällä numerolla kuin Kimmon vapaan pudotuksen nopueudet, joita oli kolme peräkkäistä ja kaikki just). to = 250/6,25/10 = 4.0

v(t) = 1000m/(1 + t/4.0s)

w(t) = 100m/s tanh(t/10.0s)

H = 1000m ln cosh (T/10s) = 10000m

T/10s - ln2 = 10 => T = 100s + 6.93s = 107 sekuntia.

Tässä ajassa ohjaamo etenee matkan

D = v(107s)n = 1000m ln (1 + 107/4) = 3323 m.

Tässä ei ole otettu huomioon ilman tihentymistä alaspäin, joka pitentää putoamisaikaa.

Se Ru MoDin 4 km ei ole mahdoton, mutta DSB:n 2.5 km on.

Tässä on kuitenkin huomattava, että 10 tonnin ohjaamoon kohdistuisi alussa maksi-mihetkellä peräti 62.5 tonnin jarrutuskuorma eli (vähän suurempi) kuin 240 tonnin Boeigin täydessä lastissa edetessä maksimiteholla nousussa. Tosin tuo "seinäänajo-jarrutus vaimemee 4 sekunnissa neljännekseen ja seraavassa 4 sekunnissa yhdeksänteen osaan alkuperäisestä maksimista.

Jos tähän asetetaan nyt putoamisen ilmanvastuskertoimksi alailmakehän arvo ρ = 1.0 , joka arvo määrää myös lopun "vakio"pudotusnopeuden ja on siten lämpänä totuutta putoamisen osalta, ja joka on ohjaamopaketin ballistisen vakion suuruinen, jos se etenee 45 sekunnissa 2.5 kilometriä, saadaan

w(t) 70.71m/s tanh(t/7.07s)

H = 500m ln cosh(T/7.07s) = 500m (T/7.07s - 0.693) = 10000m , josta

T = 7.07s (20 + 0.693) = 146 s.

Tällä saadaan etenemismatkaksi

D(T) = v(146s) = 1000m ln (1 + 146/4) = 3624 m.

Tämä on aika lähellä Almazin viimeksi piirtämää ohjaamopaketin putoamismatkaa.

Tämä on maksimaalinen "saatavilla oleva" jarrutus 10 tn:n ohjaamopaketille. Sen lyhin mahdollinen putoamismatka 10 km:n korkeusdesta ja 250m/s:n eli 900km/h:n nopeudesta on 4 km yhdellä numerolla.

***

JIT toi syyskuussa "tutkimuksissaan" julkisuuteen "venäläisen ohjusromun", ainoan lajissaan joka on löydetty noista maisemista, mutta se osoittautui Ukrainan armeijan omaisuudeksi jo vuodesta 1986 ja Venäjällä 2011 dekomissoiduksi malliksi, vaikkakin tkoi venäjällä valmistetuksi.

https://abcnews.go.com/International/missile-downed-flight-mh17-brought-russia-investigators/story

" Missile That Downed Flight MH17 Was From Russia: Investigators

An international team of investigators released its findings.

ByABC News

September 28, 2016, 9:30 PM

Photo of Likely Missile That Brought Down MH17 Released by Investigators

All 298 people on board the plane were killed in the 2014 crash.

-- A long-awaited investigation by international prosecutors has found that the anti-aircraft missile used to down Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over eastern Ukraine two years ago was transported from Russia and fired by pro-Russian separatists. The investigation’s conclusions provide the most comprehensive account of the plane’s downing, which killed all 298 aboard, and offered the most significant evidence yet of Moscow’s involvement in the supply of the missile and subsequent efforts to cover it up.

During a presentation today in Nieuwegein, the Netherlands, the joint investigation team (JIT), led by Dutch prosecutors, said it concluded “without any doubt” that the flight was hit by a powerful ground-to-air missile fired by pro-Russian rebels and that it established the missile’s route from Russia to the launch site.

“Based on the criminal investigation, we can conclude that Flight MH17 was shot down on July 17, 2014, by a BUK missile brought from the territory of the Russian Federation and that after it was launched, the system returned to Russia,” Wilbert Paulissen, a Dutch investigator, said at a news conference.

The JIT consists of representatives from Malaysia, Ukraine, Australia, Belgium and the Netherlands, which had the most citizens aboard the flight, traveling from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Recent Stories from ABC NewsThe investigators did not yet accuse Russia of sup-plying the missile, saying the next stage of the team’s investigation would focus on establishing who fired it and who gave the order. However,the JIT said it has already identified 100 individuals connected with the shooting and was working to establish levels of involvement. Although the investigation did not offer a definitive conclusion why the missile was fired, it appeared to support previous theories that the rebels shot down the airliner after mistaking it for a Ukrainian air force plane.

Russia immediately denounced the JIT investigation, launching a barrage of criticism and claims intended to dismiss the findings, with a spokesman from the country’s Foreign Ministry declaring the inquiry “biased and politically motivated.”

Since the airliner was shot down, Russian officials and state media have issued a shifting stream of contradictory explanations for the downing. Russia’s Defense Ministry first claimed the plane was targeted by a Ukrainian fighter jet and produced satellite images that were later shown to be fake. Pro-Kremlin media at one stage claimed the aircraft was packed with corpses by the CIA before it took off.

On Monday, Russia’s Defense Ministry released new radar images that it claimed showed that the missile could not have been fired by the rebels and must have come from territory under Ukrainian control. The ministry said that since its images showed no missile, it could have been fired only from Ukrainian positions.

Just an hour before the JIT delivered its findings, Dmitry Peskov, a spokesman for the Kremlin, reiterated that claim, saying it was “undeniable.”

The JIT investigators, however, refuted that, saying that not only no evidence existed to show the missile was fired from where the Russians claimed but also the evidence showing it came from rebel territory was so abundant that the radar images could not change the overall conclusion of the investigation.

“The discussion about the radar images can be concluded today,” Fred Westerbeke, the Netherland’s chief prosecutor, told reporters. “But our evidence covers a far broader scope than just radar material. We have gathered so much evidence that we can answer the question as to which weapon was used and, more importantly, exactly where this weapon was launched.”

The Dutch investigation collected and analyzed a vast amount of material, compiling it into 6,000 reports. Investigators questioned 200 witnesses, including from around the launch site, analyzed half a million videos and listened to 150,000 intercepted phone calls. The investigation reconstructed the entire front of the aircraft from fragments and carried out explosive simulations. The findings were corroborated by multiple types of evidence and backed up by previous independent investigations.

Using painstaking forensic analysis, satellite imagery, witness reports, intercepted communications and extensive reconstructions, the JIT showed that a 9M38 Buk-Telar-type anti-aircraft missile exploded in front of Flight MH17’s cockpit.

The JIT was able to reconstruct the missile’s itinerary as it was driven on a trailer from Russia to the launch site in Ukraine. Telephone conversations intercepted by Ukrainian intelligence showed rebels asking for the system to fend off Ukrainian air attacks the day before the downing. They were allegedly promised it would arrive that night.

The investigation then established the missile’s route, relying on intercepted calls, videos and photographs and witness testimonies as it wound its way through the towns of Pervomaisk and Snizhne to the launch site. Witnesses around the site described hearing the missile launched; photographs showed burn marks where the launch set the field ablaze.

Satellite imagery supplied by the European Space Agency and U.S. intelligence backed up the location. Further phone intercepts and video material, all published by the JIT, showed the missile being moved across the border from Russia.

“Given the wealth and diversity of evidence gathered by the JIT, we have no doubt whatsoever that the conclusions we are presenting today are accurate,” Westerbeke said.

Russian state media swiftly began churning out alternative theories. The Russian manufacturer of the missiles convened a press conference to claim that its simula-tions proved that the missile could have been fired only from territory controlled by Ukrainian forces, saying the Dutch had inaccurate technical data about the missile.

Russian officials suggested they were excluded from the investigation so that it could be manipulated.

“The international investigators barred Moscow from a full-fledged participation in the process of inquiry,” said Maria Zakharova, a Foreign Ministry spokeswoman.

JIT investigators said they made repeated requests to Russia for more information and that the majority of their inquiries were ignored. In his presentation, Paulissen showed that the JIT analyzed the possible launch sites indicated by the Russian military, going to exhaustive lengths to examine them.

The investigation now seeks to bring a criminal case against individuals. The JIT issued a call for witnesses, saying it was working to establish the chain of command that led to the missile’s firing. Intercepted phone calls played during the presentation suggested the plane’s downing was a mistake, with the recording appearing to show rebels confused after it happened. In a call from the day after the downing, an alleged fighter can be heard saying, “Yesterday was a mess.”

The prosecutors could not give a time frame for the investigation, but the agreement that established the JIT has been extended to 2018. A number of private lawsuits brought by victims’ relatives are underway and are expected to draw on the investigation. "

***

THE VINEYARD OF THE SAKER: NOVOROSSIAN TILANNERAPORTTI 20.9.2014

Ukraine SITREP September 20, 23:34 UTC/Zulu: War or Peace?

[Quick note: I want to begin this SITREP with a correction to something which I mentioned in the last SITREP abouy General Bezler: even though his signature did appear to figure on the infamous statement of the four commanders declaring their loyalty to "General" Korsun, the information that he had been arrested is, according so sources qualified as "solid" by Colonel Cassad, not true. Since I have no reason to doubt Cassad's sources, I assume that this is true. I have no idea why/how Bezler's signature was found on this document, maybe it was a fake? Either way, Bezler even made a short video today making fun of Ukie not-so-special forces. In contrast, Korsun's arrest is apparently confirmed. Now let's turn to the SITREP proper - The Saker]

The big event of the week was, I think, Poroshenko's speech to what I call the Imperial Senate (aka Joint Session of Congress). I have made the full transcript available here and here. I don't think that it is worth carefully parsing this text, so I will just mention the few elements which are absolutely obvious to me:

1) This text was written by a US Neocon. It even included such typical US-propagan-da gimmicks as the "personal story" to give a human touch and moment carefully crafted to generate applause. So no only what the author of this rant American, but he/she was for sure a diehard Neocon.

2) This text was a lame attempt at copying Churchill's "Iron Curtain" speech, except that Poroshenko is no Churchill, Putin no Stalin and Novorussia no Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the message was clear: Russia represents a planetary threat to freedom, democracy, liberty, human right, free speech, etc. In fact, according to Poroshenko the choice is not between two civilizations but between civilization and barbaric darkness.

3) The US deep state is by now clearly aware of the immense challenge presented to it by Putin's "Eurasian Sovereignist" Russia and the movement it leads (BRICS + SCO+etc.). The fact that it has to use such absolutely over the top rhetoric is a clear sign of fear and the Neocons are now freaking out. The danger for them is becoming very real (more about that below).

4) More than anything else, this speech proved to me that the only viable goal for Russia is regime change in Kiev. This is a message I will hammer in over and over again - regime change in Kiev is a vital, arguable existential, priority for Russia.

5) Far from being any kind of patriots or nationalists, the Ukie "nationalists" are subservient puppets of the West, willing to service AngloZionist interests with less shame then a old prostitute services her clients. For all the "Glory to the Ukraine, to the Heroes Glory!" slogans, the Ukies are the cheapest prostitutes on the planet with no self-respect whatsoever.

The entire speech had a Disney-like feel to it: on one side, the forces of Light, lead by the USA in white shining armor and on the other, the forces of Darkness, lead by Russia crawling out of the Asian steppes like Lovecraft's Chtuhlu. Infantile to the extreme, the purpose of the speech was to induce a planetary war against Russia and her allies or, at the very least, to contain that 21st century Mordor. Poroshenko went as far as referring to now completely disproved lies (such as Russia invading Georgia in 2008) and hinting that Moldova, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Baltic States, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria. could/would be next. Clearly the main can lie with an ease which any used car salesman would envy.

Then there is the issue of the standing ovations. Less than Obama and less than Netanyahu, but still a lot (12 I think). The Imperial Senators appeared to stand longer and clap harder each time Poroshenko drifted off into some kind of crazy nonsense. A scary sight, really.

Now we all know who runs the US Congress (AIPAC) so what this is, really, is a declaration of war by AIPAC and the Zionist faction of the AngloZionist Empire. The Anglos are far less enthusiastic as shown by Obama's refusal to send weapons to the Ukies. Just like in 2008 and that other lunatic - Saakashvili - I get the feeling that there might be a lot of behind the scenes Neocon "parallel diplomacy" going on. If not, why would Obama's bosses tell Poroshenko to ask for weapons they don't want to give him in the first place? My guess is that there is a lot of reluctance in the Pentagon and possibly in the intelligence community to get the USA fully committed behind a regime which might not be around in a few months.

Whatever may be the case, Poroshenko's speech felt like an infantile but nasty declaration of war. Clearly, there are those who are very concerned that peace might break out

On the "peace front" a number of interesting things happened. First, on September 14th sixteen business representatives from the USA, Russia, Germany and the Ukraine met for a private meeting with the Chairmen of the World Economic Forum Klaus Schwab. In attendance were some very big player including the hyper-notorious Anatolii Chubais (for a complete list or participants, see here).

They adopted the following document:

(You can also download the document from here.) The publication of this document resulted in something as predictable as it was amazing. The "Putin is selling out No-vorussia" choir immediately denounced this document as a total betrayal of Novorus-sia and a victory for the oligarchs. I said that this was a predictable reaction because by now it is pretty clear that these folks will denounce any and all negotiated docu-ments (Agreement,Memoranda,Treaty or any other type) as a "sellout of Novorussia" , "victory for the oligarchs" and "capitulation by Putin". Still, what was absolutely amazing to me that apparently they seem to notice #6:

Guarantee the security and sovereignty of Ukraine by the international community. Recognize the supremacy of international law above national interests. Recognize the right of self-determination but encourage to consider a policy of military non-alignment for Ukraine, comparable to the status of other European countries (i.e. Finland, Sweden, Switzerland).Amazingly,but the nay-sayers managed to completely miss the fact that 1) Ukie laws which contravene the EU Convention on Human Rights (including Protocol 12 on minority rights) and the UN Charter (whose Article 1 and others specifically uphold the right of self-determination) could be overruled 2) that the Ukies were told to recognize the right of self-determination (not just federa-tion, but open-ended self determination) and 3) that the Ukies were told that they will have to remain neutral and non-aligned.

And that, coming form Chubais & Co!

Now,I understand that the Ukies broke every single document they signed so far,and this one will be no exception. But what is crucial here is that the message from "top finance" is not Poroshenko's hysterical call to arms before the Imperial Senate, but "no crazy laws, self-determination, no NATO". This is a HUGE victory for Russia who sees a Ukrainian membership in NATO as a major threat. Conversely, this WEF Initiative is a nightmare come true for the Neocons as it finalizes, if it is applied of course, the non-NATO status for the Ukraine.

True, this document speaks of a unitary Ukrainian state (apparently unless and until the right of self-determination trumps that) and it is full with well-meaning generali-ties. But point #6 is absolutely amazing coming, as it does, from the transnational plutocrats which signed it. And yes, will Chubais' friend recommend an non-block status for the Ukraine, the Ukie Rada is abrogating its nonaligned while Timoshenko demands and entry into NATO.

Finally, keep in mind that this is an "initiative" which does not commit the Ukraine or Russia to anything. At most, this is a declaration of desirable principles, a basis for negotiation if you want.

Version 2:

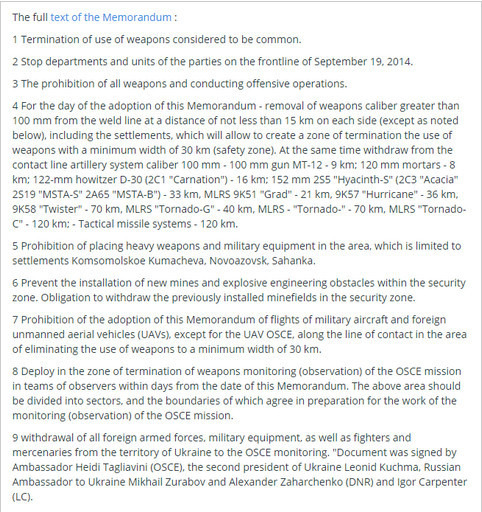

The other big event of the week is signing of the Minsk Memorandum. Here is the full text:

Unlike the vague and, frankly, un-implementable Minsk cease-fire agreement, this Memorandum provides some perfect reasonable standards by which to measure compliance by both parties. Some points are politically correct nonsense (#9) but most of this text can be summarized as following: a "freezing" of the conflict along the line of contact. Is that good or bad?

Strelkov immediately denounced that Memorandum in the strongest possible terms. According to Strelkov, this is a victory for the "betrayal" camp lead by Surkov who has deceived Putin and is now pushing him into a Milosevic-type of scenario. In contrast, Zakharchenko, obviously, full backs the plan. So let's look a bit closer to this Memorandum.

For one thing, and that is important, it contains exactly zero political provisions. None. So the first rather obvious point that I would like to make is that this plan is very limited in scope: all it does is provide the basis for a mechanism to achieve a more or less verifiable ceasefire. Period. So if the Minks Ceasefire Agreement was list of vague and unenforceable (I would even argue undefined) general political statements, this document is the extreme opposite: a purely technical tool which really codifies the current situation on the ground.

So what is the political context in which this ceasefire will have to be observed? What is the point of the ceasefire?

Well, again, that depends whom you ask.

According to Poroshenko and other Ukrainian officials it is to give time to the Junta Repression Forces (JRF) to regroup, reorganize and prepare for a counter-attack. Strelkov would agree. Zakharchenko and Lavrov disagree. While they observe and denounce the Ukie preparations for a possible (likely? inevitable?) counter-attack, their official position is that the Agreement and the Memorandum are now binding documents useful in preparation for a final status negotiations. At this point Zakharchenko speaks of a completely independent Ukraine and Lavrov of a neutral Ukraine respectful of all its citizens.

I suggest we take it step by step.

First, long before we got to this point, we used to have heated debates on this blog about whether time was on the Russia, Novorussian or Ukie side. At the time, most commentators, including myself, were of the opinion that time was most definitely on Russia's side,but the question was if Novorussia could survive long enough. Basical- ly, we wondered if Novorussia could stay alive long enough for Banderastan to col-lapse,or whether the only way to save Novorussia from a Nazi takeover was an overt Russian military intervention in the Donbass. Some of us even spoke of weeks.

Now, several months later, we see that not only did Novorussia not collapse under a Nazi takeover, but that the Novorussian Armed Forces gave a magnificent thrashing to the JRF and instead of getting encircled in Donetsk and Lugkans,the NAF pushed the JRF all the way out to Mariupol. At the very least, this proves that

1) Those who said that a Russian military intervention was the only way to save Novorussia were wrong: Novorussia survived.

2) Those who said that there was no Russian covert aid or that this aid was insuffi-cient were wrong again:Voentorg is thriving (named after a military store, "voentorg", which literally means "military trade", here refers to the Russian covert aid to Novorussia)

Furthermore, at the time everybody agreed that things could only get worse for Ban-derastan, especially when the Fall and Winter would begin. As far as I know, there is still nobody predicting a miraculous turn-around in the Ukie economy so we can as-sume that all that Banderastan did was get so much closer to the inevitable econo-mic and social cliff.And, indeed,the cracks are visible all over,AngloZionist aid or not.

I think that basic logic tells us that time is still on Russia's side and that the Ceasefire Agreement, this time supported by a Memorandum, solves the time problem for Novorussia: with aid from Russia freely flowing in (both over humanitarian aid and covert, "voentorg", aid) Novorussia can now sit tight and wait. The cold season will not only exacerbate the economic-social tensions in Banderastan, it will also make offensive operations much harder.

What about the opportunity costs?

In economics there the notion of "opportunity costs". These are the costs you do not incur directly (you don't have to pay anything), but these are the "costs" resulting from missed opportunities. Income you could have made, but did not.

Is Novorussia incurring such opportunity costs as the result of this peace?

That depends on your hypothesis.

There are those who believe that the NAF could if not make it to Kiev, then at least liberate Mariupol, Dnepropetrovsk, Kharkov and other cities. I agree that Mariupol was about to fall, but only at great risk of envelopment from the north. As for other cities, I personally don't believe that is true. Even Slaviansk is quite out of reach, at least for the time being.Some say that a collapse of the JRF would have left the road open to Kiev. While true in one sense (some units might have used to panic to make it that far), this is a typically civilian idea of warfare. "Getting there" can be easy, of course, but it's *staying* there typically turns into a nightmare. I do not believe that by early September the NAF had the capabilities to breakout much beyond their current areas of deployment and to successfully liberate much more territory.

Furthermore, I do not believe that a purely military solution is achievable, especially not one which has Novorussians "liberating" central or, even less so, western Ukraine. I know that my hatemail will go through the roof, but I will say that I think that freezing the frontline on September 19th is a pretty good deal, especially since that removes the single biggest "distraction" in internal Ukie politics: the so-called "Russian invasion".

There are also those who say that the Russian military could liberate most, or even, all of the Ukraine. I agree. Militarily,this is a no-brainer. But by doing so Russia would provide the Neocons with their ultimate dream: a Cold War v2 for many decades to come.Pragmatically,this would be a disastrous decision.But the moral aspect is even more important here. As far as I am concerned, and setting aside all my sympathy for the people of Novorussia who have fought for their freedom and, I am now con-vinced of it,will get it, Russia owes the Ukraine absolutely nothing. Not gas, not loans and most definitely not the lives of Russian soldiers.There is no reason I can think of why a young man from Moscow, Tobolsk or Makhachkala has to sacrifice is life libe-rating Banderastan from the local Nazis. No, sorry, the Ukrainians have to free them-selves. It is the hight of hypocrisy to spend decades whining about the Moskals and then expect them to come a liberate you from your own Nazi freaks.

The people of Donetsk and Lugansk have shown that they, like the folks of Crimea or South Ossetia,are truly deserving of Russian help,even if that means that Russian young men should die, as happened in South Ossetia. And I would note here that South Ossetian man are now fighting as volunteers for Novorussia, so the Ossetians have proven beyond any doubt that they were fighting for.

But the folks in the rest of (historical) Novorussia?

Did you hear about the uprising in Mariupol? Right.Neither did I. What about the par- tisans around Zaporozhie or Chernigov? Same thing. Well, in reality, this is not quite true and not really fair. First, the Nazis are using terror to subdue the locals in these cities and, second, there have been a few actions here and there. But if Strelkov was speaking the truth when he said that most young men in Donetsk and Luganks were quite happy to sip beer and watch the events on their idiot-boxes, this is even much more true of the rest of the Ukraine. Even senior NAF commander admitted that their strength was in the fact that the NAF were liberators, but that the further they would go west, the more they would be seen not as liberators but as occupiers (and, be-lieve me, the propaganda on Ukie TV is nothing short of unimaginable: according the Ukie officials who speak on Ukie TV on a daily basis, Russia is already occupying the Ukraine with, last time I heard, 19 battalion tactical groups!)

Every one is free to have his/her opinion and I cannot prove that I am right simply because hypotheticals are, by definition, unprovable. But my personal belief is that freezing the line of contact on the 19th is reasonable and that the ceasefire benefits everybody more than the regime in Kiev (which is why I expect it to be broken even more than it already is). Furthermore, I submit that these are the fundamental objectives of the key parties to this civil war:

1) Russia: regime change in Kiev (long term goal: years)

2) Novorussia: de-facto full independence from Kiev (short term goal: months)

3) rest of the Ukraine: liberation and full de-Nazificaton (long term goal: years)

The current situation is favorable for #1 and #2.

What about the warning from Strelkov: that this ceasefire agreement is like the one reached in Croatia which gave the Croats time to prepare a counter-attack with their NATO masters and (illegally) occupy the Serbian Krajinas?

For all my sympathy and admiration for Strelkov, I think that he is plain wrong.