" Religious views

Trump is a Presbyterian.[518] He has said that he began going to church at the First Presbyterian Church in the Jamaica neighborhood in Queens as a child. Trump at- tended Sunday school and had his confirmation at that church.In an April 2011 inter- view on the 700 Club, he commented: "I'm a Protestant,I'm a Presbyterian. And you know I've had a good relationship with the church over the years. I think religion is a wonderful thing. I think my religion is a wonderful religion. ...Trump has said that al-though he participates in Holy Communion,he has not asked God for forgiveness for his sins. He stated,"I think if I do something wrong,I think,I just try and make it right. I don't bring God into that picture. "

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presbyterian_Church_(USA)#Presbytery

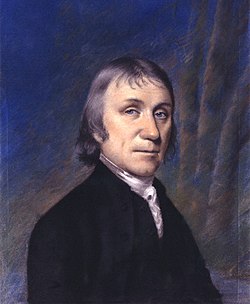

Many Prebyterians have been Unitarians who do not accept the Holy Trinity, like for instance one central founder chemist Joseph Priestley, one inventor of oxygen:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unitarianism

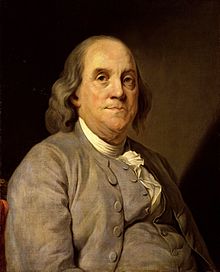

Presbyterian Church had important role in the US struggle of independence: Its lea- der William Witherspoon and a Priestley´s scientific follower, President on Pennsyl-vania, factually Presbyterian Benjamin Franklin were members on the Founding Father of the United States, and Priestley and some others were ministers. Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

Presbyterian Church has interesting connection to the scientific concept of man

David Hartley´s neurophysiologically justified imagination of the linguistic nature of personality (nowadays Pavlov´s second signaalin system) is included by Joseph Priestley into the canon:

http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Hartley%2C+David

Hartley, David

Also found in: Dictionary, Thesaurus, Wikipedia.

Hartley, David, 1705-57, English physician and philosopher, founder of associational psychology. In his Observations on Man (2 vol. 1749) he stated that all mental pheno- mena are due to sensations arising from vibrations of the white medullary substance of the brain and spinal cord. He conceived the whole mind as resulting from the association of simple sensations. See associationism.

The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia™ Copyright © 2013, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Columbia University Press. All rights reserved. www.cc.columbia.edu/cu/cup/

Hartley, David

Born Aug. 30, 1705, in Armley; died Aug. 28, 1757, at Bath. English thinker; one of the founders of associationist psychology.

A clergyman’s son, Hartley studied theology at Cambridge. Later on he received a medical education and practiced medicine all his life.

Striving to establish the precise laws of mental processes for controlling human be- havior, he sought to apply the principles of Newtonian physics for that purpose. Ac- cording to Hartley, vibrations of the outer ether cause cor- responding vibrations in the sense organs, brain, and muscles, and the latter are in a relationship of paralle- lism to the order and connection of mental phenomena, from elementary sensations to thought and will. Pursuing the theory of J.Locke,Hartley for the first time made of the mechanism of asso- ciation the universal principle for explaining mental activity. He considered repetition to be fundamental for the reinforcement of association. As Hartley saw it, the mental world of the individual takes shape gradually as a result of the complication of primary elements through association of mental phenomena by virtue of their contiguity in time and frequency of repetition; the motive forces of de- velopment are pleasure and pain. Hartley in like fashion explained the formation of general conceptions; these arose out of individual conceptions through the gradual disappearance of everything fortuitous and unessential from an association, which remains immutable; all of its constant features are retained as an integral whole thanks to speech, which acts as the factor of generalization.

Though mechanistic, Hartley’s theory was a major step forward on the way to a materialistic interpretation of the mind. He influenced not only psychology but ethics, aesthetics, logic, pedagogy, and biology as well.

The English chemist and philosopher J. Priestley vigorously propagated Hartley’s teachings. "

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Priestley

" Joseph Priestley: Presbyterian minister, scientist and metaphysician. Wrote several books on Unitarianism and established the first Unitarian Church in America. (1733 - 1804) "

I’ve been writing about the on-again, off-again correspondence of Benjamin Franklin and David Hartley, British scientist and Member of Parliament. Their relationship actually turned out to be a factor in the end of the war.

After London received news of the Battle of Yorktown, Lord North’s government fell. In March 1782 power shifted to the Marquess of Rockingham, longtime leader of the opposition, with a mandate to bring the American War to a close before it cost even more money. Rockingham filled the post of prime minister for all of four months before he died of the flu.

The Earl of Shelburne, one of Rockingham’s secretaries of state, took over. He was already steering negotiations with the U.S. of A.’s European diplomats through his envoy, the merchant Robert Oswald. By November 1782 Oswald worked out preliminary articles of peace with Franklin in France.

Meanwhile, Rockingham’s other secretary of state, Charles James Fox, refused to serve under Shelburne. He led other Rockingham Whigs, such as Edmund Burke, out of government. (That created openings for such rising politicians as William Pitt, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer at the age of twenty-three; they didn’t call him “the Younger” for nothing.)

David Hartley had opposed the American War all along, but he also disliked Shel- burne and voted against the preliminary articles for peace. Hartley was a Fox ally, and he also maintained a personal friendship with Lord North, despite their political differences.

In April 1783 Fox and North, longtime opponents,made a surprising alliance to force Shelburne out of power. Shortly afterwards, George III appointed Hartley the new negotiator with the Americans. Fox and North both trusted Hartley, and they thought his friendly correspondence with Franklin would help to finish the negotiations on favorable terms.

Hartley walked into a very complex situation since France, Spain, and the U.S., though formally allied and bound to negotiate together, were all secretly angling for their own advantages and undercutting each other. Though there weren’t any more major campaigns on the North American continent, naval battles in the Caribbean and the siege of Gibraltar were still going on, tipping the balance of power and affecting different nations’ hunger for peace.

The Americans in Paris insisted on making very few changes to the terms they had reached with Oswald. If Hartley wasn’t going to sign over Canada, they weren’t about to concede anything else. France and Spain, meanwhile, thought the Shelburne ministry’s agreement to give the new American republic land all the way west to the Mississippi River was quite generous already.

In the end, the Treaty of Paris was basically what Oswald had negotiated eight months earlier. Hartley had voted against those terms, but his main contribution to the final treaty was the “Paris” part — he refused to leave the city for Versailles. On 3 Sept 1783, Hartley signed the final Treaty of Paris on behalf of Great Britain. Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay signed on behalf of the U.S.

(The picture below is Benjamin West’s famous unfinished canvas of the American diplomats involved in the negotiations in Paris. Hartley declined to pose.)

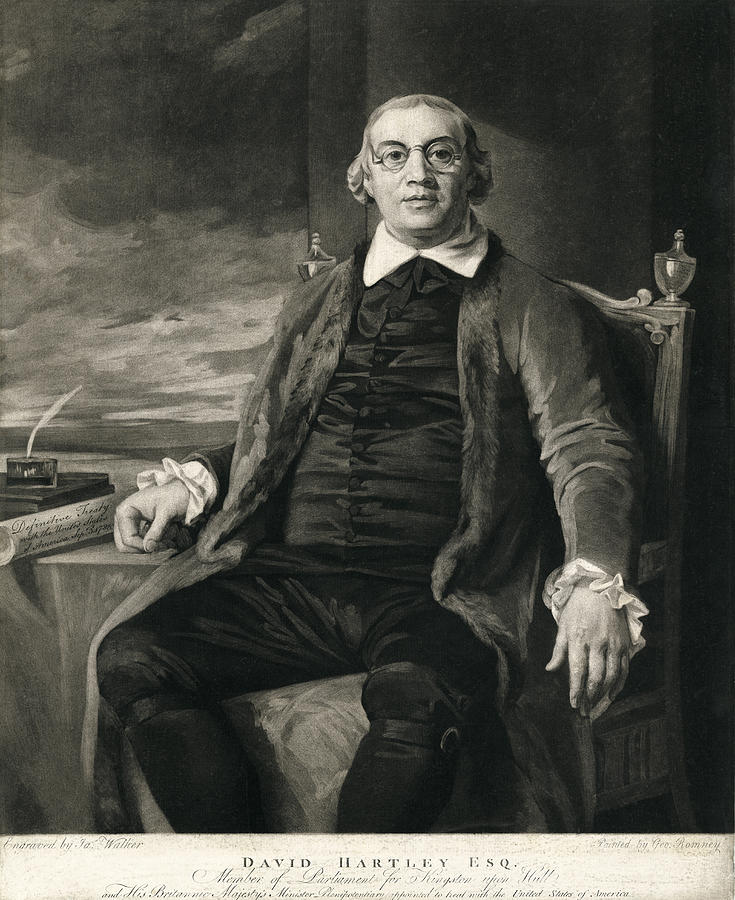

MP David Hartley Jr. (1732 - 1813)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hartley_(the_Younger)

David Hartley (the Younger)

David Hartley the younger (1732 - 19 December 1813) was a statesman, a scientific inventor, and the son of the philosopher David Hartley.He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Kingston upon Hull, and also held the position of His Britannic Majesty's Mi-nister Plenipotentiary, appointed by King George III to treat with the United States of America as to American independence and other issues after the American Revolu-tion. He was a signatory to the Treaty of Paris.Hartley was the first MP to put the case for abolition of the slave trade before the House of Commons,moving a resolution in 1776 that "the slave trade is contrary to the laws of God and the rights of men". [1]

Life

Hartley was born in Bath, Somerset, England in 1732. He matriculated at Corpus Christi College,Oxford on 6 April 1747 at the age of 15.He was awarded his B.A. on 14 March 1750 and was a fellow of Merton College, Oxford until his death. He be- came a student of Lincoln's Inn in 1759.During the 1760s he gained recognition as a scientist and, through mutual interests, he met and became an intimate friend and correspondent of Benjamin Franklin. Hartley was sympathetic to the Lord Rocking- ham's Whigs, although he did not hold office in either Rockingham ministry.He repre- sented Kingston upon Hull in parliament from 1774 to 1780, and from 1782 to 1784, and attained considerable reputation as an opponent of the war with America, and of the African slave trade.

He was expert in public finance and spoke frequently in parliament in opposition to the war in America. Although a liberal on American policy, Hartley was a long-time friend of Lord North and strongly disliked the Prime Minister, Shelburne. He suppor- ted the Coalition by voting against Shelburne's peace preliminaries. It was probably owing to his friendship with Benjamin Franklin, and to his consistent support of Lord Rockingham,that he was selected by the government to act as plenipotentiary in Pa- ris, where, on 3 September 1783, he and Franklin drew up and signed the definitive treaty of peace between Great Britain and the United States.

Hartley died at Bath on 19 December 1813 in his eighty-second year.

His portrait was painted by George Romney and has been engraved by J. Walker in mezzotint. Nathaniel William Wraxall says that Hartley,"though destitute of all perso- nal recommendation of manner,possessed some talent with unsullied probity, added to indefatigable perseverance and labour". "He adds that his speeches were intole- rably long and dull, and that "his rising always operated like a dinner bell" (Memoirs, iii. 490).

Writings

Hartley's writings are mostly political, and set forth the arguments of the extreme libe- rals of his time. In 1764 he wrote a vigorous attack on the Bute administration, "in- scribed to the man who thinks himself a minister." His most important writings are his Letters on the American War, published in London in 1778 and 1779, and addressed to his constituents. "The road," he writes, "is open to national reconciliation between Great Britain and America. The ministers have no national object in view ... the object was to establish an influential dominion of the crown by means of an independent American revenue uncontrolled by parliament." He seeks throughout to vindicate the opposition to the war. In 1794 he printed at Bath a sympathetic Argument on the French Revolution, addressed to his parliamentary electors.

Hartley edited his father's well-known Observations on Man, in London 1791 and (with notes and additions) in 1801.

In 1859 a number of Hartley's papers were sold in London. Six volumes of letters and other documents relating to the peace went to America and passed into the collection of L.Z. Leiter of Washington, D.C.; others are in the British Museum.

Princeton Unversity as "Presbyterian University"

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States.

Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton was the fourth chartered institution of higher education in the Thirteen Colonies[7][a] and thus one of the nine colonial colleges established before the American Revolution. The institution moved to Newark in 1747, then to the current site nine years later, where it was renamed Princeton University in 1896.[12]

Princeton provides undergraduate and graduate instruction in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and engineering.[13]It offers professional degrees through the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, the School of Engi- neering and Applied Science, the School of Architecture and the Bendheim Center for Finance. The university has ties with the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Theological Seminary, and the Westminster Choir College of Rider University.[b] Princeton has the largest endowment per student in the United States.[14]

The university has graduated many notable alumni. It has been associated with 42 Nobel laureates, 21 National Medal of Science winners14 Fields Medalists, the most Abel Prize winners and Fields Medalists (at the time of award) of any university (five and eight, respectively), 10 Turing Award laureates, five National Humanities Medal recipients,209 Rhodes Scholars,and 126 Marshall Scholars.[15] Two U.S.Presidents (James Madison 1809-18117, Woodrow Wilson), 12 U.S. Supreme Court Justices (three of whom currently serve on the court), and numerous living billionaires and foreign heads of state are all counted among Princeton's alumni. Princeton has also graduated many prominent members of the U.S. Congress and the U.S. Cabinet, including eight Secretaries of State, three Secretaries of Defense, and two of the past four Chairs of the Federal Reserve.

4th President of the United States

In office

March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817

New Light Presbyterians founded the College of New Jersey in 1746 in order to train ministers.[16] The college was the educational and religious capital of Scots-Irish America. In 1754, trustees of the College of New Jersey suggested that,in recognition of Governor's interest,Princeton should be named as Belcher College. Gov. Jonathan Belcher replied: "What a hell of a name that would be!" [17] In 1756,the college moved to Princeton, New Jersey. Its home in Princeton was Nassau Hall, named for the royal House of Orange-Nassau of William III of England.

Following the untimely deaths of Princeton's first five presidents, John Witherspoon became president in 1768 and remained in that office until his death in 1794. During his presidency, Witherspoon shifted the college's focus from training ministers to preparing a new generation for leadership in the new American nation. To this end, he tightened academic standards and solicited investment in the college. [18] Wither-spoon's presidency constituted a long period of stability for the college, interrupted by the American Revolution and particularly the Battle of Princeton, during which British soldiers briefly occupied Nassau Hall; American forces, led by George Washington, fired cannon on the building to rout them from it.

Woodrow Wilson, U.S. President 1912-21, Princton University President 1902-10, historician, Peace Nobelist 1919.

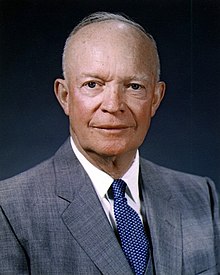

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | |

|---|---|

| |

| 34th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1953 – January 20, 1961 |

While speaking of himself in 1948, Eisenhower said he was "one of the most deeply religious men I know" though unattached to any "sect or organization". He was baptized in the Presbyterian Church in 1953.[21]

British Arianism:

Looks briefly at anti‐Trinitarian tendencies in sixteenth‐ and seventeenth‐century Britain (with special attention to Ralph Cudworth and John Locke), but concent-rates on the eighteenth century, when Arianism was a significant feature of the ec-clesiastical scene, especially among leading intellectual figures both in the Church of England and among the Presbyterian churches. Detailed studies of the theolo- gies of Isaac Newton, William Whiston,and Samuel Clarke. Traces the collapse of this Arian‐style anti‐Trinitarianism in the Church of England and the tendency of he-terodox dissenters, such as Joseph Priestley, to adopt a Unitarian view. Suggests that the diminishing acceptance in the wider culture of belief in a transcendental spirit world was an important factor in that tendency, leading to a third death of Arianism.

Keywords: Clarke, Cudworth, Locke, Newton, Presbyterian, Priestley, spirit world, Unitarian, Whiston

Oxford Scholarship Online requires a subscription or purchase to access the full text of books within the service. Public users can however freely search the site and view the abstracts and keywords for each book and chapter.

http://www.romeroinstitute.org/docs/Week%204/The+Scottish+Enlightenment+and+the+American+Founding.pdf

THE SCOTTISH ENLIGHTENMENT AND THE AMERICAN FOUNDING

Writing to Thomas Jefferson from his modest residence in Quincy, Massachusetts, John Adams begins what will be an interesting philosophical colloquy with these lines:

Montezillo Febraary 21st 1820

Dear Sir, Was you ever acquainted with Dugald Stuart?... I have a prejudice against what they call Metaphysicks because they pretend to fathom deeper than the human line extends. I know not very well what e'er the to metaphusica of Aristotle means, but I can form some idea of Investigations into the human mind, and I think Dugald in his Elements of the Philosophy of the human mind has searched deeper and reasoned more correctly than Aristotle, Des Cartes, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Condillac and even Reid.'

The year is 1820.Adams and Jefferson,no longer in the pitch of political battle, have turned their attention to a wide range of intellectual matters and have begun yet an-other reflection on the assumptions and implications associated with the American Revolution. Within this context, there is nothing unusual about the two greatest lea-ders of American political sensibilities citing Reid and Stewart and even giving Reid pride of place in a list that includes Descartes, Locke, and Hume. By 1820 the debt of the Founders to Scottish moral and mental philosophy was widely acknowledged and repaid chiefly in the currency of admiration and discipleship. No brief essay can reach the range and contours of the debt.Rather,some illustrations and an assortment of not very well integratedfacts might serve as guide and reminder.

There is, of course, no decisive point of origin with inquiries of this sort. As early as 1560 the First Book of Discipline of the Church of Scotland had declared that mi-racles had run their course. Now put on notice,the Christian must make his own way and this chiefly through diligence and,yes,systematic education. The resulting model of Scottish education, with its distinctively "humanistic Calvinism," was widely adop-ted in American colonies and then in the States of the Union. At the time ofthe Ameri-can Civil War (1861), there were 207 colleges and universities, of which 49 had been founded by Presbyterians. The influence of this educational mission was diffuse and powerful, all the more so given the relative absence of credible alternatives. It was common for American faculties to appoint Scottish tutors or those educated in Scot-land. At William and Mary, for example, Jefferson was introduced to the works of his greatest heroes - Locke, Bacon, and Newton - by William Small, a graduate of Mari-chal College, Aberdeen.Small returned to England in 1764 and was a central figure in that Lunar Society whose members included James Watt, Josiah Wedgwood, Erasmus Darwin,and Joseph Priestley.It is difficult to exaggerate Small's influence on young Thomas Jefferson who would write this about his teacher:

Dr. Small was ... to me as a father. To his enlightened and affectionate guidance of my studies while at college, I am indebted for everything.... He procured for me the patronage of Mr. Wythe, and both of them, the attention of Governor Faquier.... [A]t their frequent dinners with the governor.... I have heard more good sense, more rational and philosophical conversation than all my life besides.^3

Perhaps it is worth noting also that Small's own education at Marichal College was chiefly in the hands of William Duncan who, as a student there himself, studied Clas-sics from Reid's own tutor, Dr. Blackwell. Duncan became well known for his fine translations of Cicero and of Caesar's Commentaries. (I ignore here the question of whether Duncan's text in Logic had any influence on Jefferson's draft ofthe Declara-tion of Independence).To speak ofthe influence ofthe Scottish Enlightenment on edu-cation in America is at once to speak of Princeton whose legendary Scottish presi-dent, John Witherspoon (1723-1794), would become a signer ofthe Declaration of Independence. He not only presided over Princeton, he was an active and energetic teacher who personally instructed entire graduating classes. His students included the fiiture President of the United States, James Madison, as well as nine cabinet officers, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine members of the House of Representatives, a dozen State governors, five ofthe fifty-five delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and three Justices ofthe U.S. Supreme Court.

Witherspoon was a graduate of Edinburgh University, later awarded an honorary Doctorate from St Andrews in 1764. Within the Church of Scotland, he had already made a name for himself as a leader of the so-called "Popular Party," the party of conservative evangelicals. Thus, long before he would come to take so significant a part in the American cause, he had a clear conception of the need to protect religion from the reach of govemment, but not fi-om the reach of reason. As a teacher and educational reformer, he broadened and deepened the traditional curriculum, intro-duced new and daring philosophical ideas, enlarged and diversified the library hol-dings, and acquired fine apparatus for scientific studies. Known to be a graceful and eloquent speaker, he was possessed of a useful sense of humour as well. An insom-niac given to post-prandial dozing, he failed to have the legislature of New Jersey move its meetings to an earlier hour. Apologizing in advance for the naps he knew he would be taking, he informed the assembly thus:

There are two kinds of speaking that are very interesting . . . perfect sense and per-fect nonsense. When there is speaking in either of these ways I shall engage to be all attention. But when there is speaking, as there often is, halfway between sense and nonsense, you must bear with me if I fall asleep.^4

Witherspoon's pivotal role was not limited to his innovations and influence as an edu-cator, but extended directly to the political arena at the very moment when indepen-dence was to be established. The day was July 4, the year 1776, and the venue what came to be called "Independence Hall," Philadelphia. On the table was the Declara-tion of Independence, adopted two days earlier but now in a chamber rather chilled and hushed by forebodings. Rising to the occasion, Witherspoon proclaimed that:

There is a tide in the affairs of men, a nick of time. We perceive it now before us. To hesitate is to consent to our own slavery. That noble instrument upon your table, which ensures immortality to its author, should be subscribed this very morning by every pen in this house.He that will not respond to its accents and strain every nerve to carry into effect is provisions is unworthy the name freeman. For my own part, of property I have some, of reputation more. That reputation is staked, that property pledged, on the issue of this context; and although these gray hairs must soon des-cend into the sepulchre, I would infinitely rather that they descend thither by the hand of the executioner than desert at this crisis the sacred cause of my country.

Witherspoon's emigration from Scotland was initially postponed as a result of his wife's fear of travel and relocation, especially to a world she judged to be barbarous. It may be said that her resistance was overcome in part by the insistent urging of a young American studying medicine at Edinburgh at the time, viz., Benjamin Rush (1746 - 1813).

Rush had graduated from the then College of New Jersey in 1760 when a mere fif-teen years old. After a medical apprenticeship in Philadelphia, he went on for formal medical education at Edinburgh in 1766, there studying with Joseph Black and John Gregory and becoming both a disciple and good friend of William Cullen. Cullen's friendships and collegial associations included Adam Smith, David Hume, and Cul-len's own patron. Lord Kames. Rush was not the only American to be inftuenced by Cullen's empirical approach to medicine and science, for there was even a more famous disciple at a distance — Benjamin Franklin.

Rush's other teacher, John Gregory was Thomas Reid's cousin, a member of Reid's "Wise Club" and a bearer of that Scottish Common Sense philosophy for which Reid had recently and justly become famous.The question often asked is whether Thomas Paine's best-selling pamphlet. Common Sense, was at all indebted to Reid. It is suffi-cient to note that it was Benjamin Rush who actually gave the title to Paine, though Rush would not be entirely supportive of the contents.* There is no doubt but that Rush's achievements as a reformer in medicine were deeply grounded in the studies and relationships at Edinburgh. He would come to be hailed as the "Father of Ameri-can Psychiatry" by the American Psychiatric Association. His writing on psychologi-cal disorders,their medical and contextual determinants, closely track Cullen's celeb-rated Nosology. nHe was founder of Philadelphia's Dispensary for the Poor, the foun-der of Dickenson College, and the author of the first textbook in psychiatry written in the new world: Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812). His avid and relentless efforts in behalf of the abolition of slavery also were fortified during the Edinburgh years. Needless to say, opposition to slavery required no colonial importation of ideas, for the institution was judged repugnant by a number of home-grown luminaries. But Rush's scientific and philosophical cast of mind was well served by the Scottish systematic approach to moral issues.Infiuential within this genre was Francis Hutcheson's A System of Moral Philosophy (1755),which gave fijil expression to Grotius and Puffendorf as Natural Law theorists and which rendered logically and morally incoherent an institution of slavery within any context otherwise supportive of human rights.

Less well known now than Hutcheson's writing but perhaps at least as influential in the second half of the eighteenth century was David Fordyce's The Elements of Mo-ral Philosophy. The work was published posthumously in 1754. Fordyce (1711-1751) was yet another remarkable Aberdonian, having died at sea several years earlier.

Thus, he did not live to take satisfaction in the importance that would be attached to this work in the Colonies. It was an immediate fixture in the Harvard curriculum and soon a preferred text throughout colonial higher education. In Book II, Chapter IV of that work the author calmly traces the relationship between master and servant to that "natural course of human affairs" which episodically finds opulence and poverty crea-ting class distinctions. But reciprocity is the rule of reason in such affairs, such that persons of privilege require the labor of those who, owing to poverty, need such work. Speaking of the servant, Fordyce insists that.

By the voluntary Servitude to which he subjects himself,he forfeits no Rights but such as are necessarily included in that Servitude. .The offspring of such Servants have a Right to that liberty which neither they, nor their Parents, have forfeited [emphasis in original].'' Clearly, slavery as such is understood as the corruption of the natural rela-tionship, the woeful vice of it made by its hereditary extension. Later in the work, For-dyce, considering the terms of civil society and political authority, offers a judgment that could not help but give principle to colonial enthusiasms: As the People are the Fountain of Power and Authority, the original Seat of Majesty, and Authors of Laws, and the Creators of Officers to execute them; if they shall find the Power they have conferred abused by their Trustees, their Majesty violated by Tyranny, or by Usurpa-tion, their Authority prostituted to support Violence, or screen Corruption, the Laws grown pernicious through Accidents unforeseen . . . then it is their Right, and what is their Right is their Duty, to resume that delegated Power, and call their Trustees to an Account. 8

Turning now to matters of law, of delegated authority, and of rights, the name that summons perhaps the greatest attention is James Wilson (1742-1798), bom near St Andrews where he was educated, as well as at Glasgow and Edinburgh. More than the customary space is reserved here for Wilson because in his writing and his thought one is able to locate the rich amalgam of the discipline of law and that Scottish Common Sense philosophy committed to a naturalistic, no-nonsense empi-ricism resistant to linguistic sources of confusion and idle invention. The space devo- ted to Wilson,then,is earned by his pivotal role at the Founding,hut also hy his exem-plification of the broader influences under consideration here. All this comes into focus in a truly pivotal case (vide infra) decided by the first U.S. Supreme Court with Wilson giving the most disceming of the opinions. Ambitious and adventurous, Wilson emigrated to the Colonies in 1766 tuming to the study of law under John Dic-kenson of Philadelphia. He thereafter established a successful law practice and rea-dily entered into the revolutionary political climate of the time. A pamphlet of his com-posed in 1774 gave him intemational celebrity. Titled Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament, the work included the uncompromising claim that "all men are by nature equal and free." Though his life would prove to he a checkered one, Wilson was second only to James Madison him-self in exercising control and rallying consensus in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. It is probably the case that his speech of October 6,1787, rging the ratification of the Constitution, was more widely read and perhaps even more successful in its aims than The Federalist papers.' Two years later, George Washington appointed James Wilson to the first U.S. Supreme Court where he served as Associate Justice.

In his capacity as Supreme Court justice, Wilson both shapes and sheds light on the emerging jurisprudence of the new nation. It is useful to consider one of the major ca-ses settled by the Court in Wilson's time, and the grounds which Wilson himself took to bedispositive. It is a well known case in U.S. Constitutional history, for it addressed the significant question of the immunity of individual States to actions brought against them by citizens. The case is Chisolm v Georgia, settle in 1793.'° In this action, the State of Georgia claimed sovereignty, and thus immunity to actions brought against it in a Federal court.

The terms of the dispute were novel, raising the question of whether a State could be sued by the resident of another State. Alexander Chisolm was a citizen of South Ca-rolina and executor of the estate of one Robert Farquahar. The latter had sold uni-forms to Georgia for its Revolutionary War effort but had not heen compensated. The Continental Congress, fore-runner of the new U.S. Congress, had established each State as sovereign and thus immune to actions arising in another jurisdiction. Even more than John Jay,Wilson understood the gravamen of the State's claim, noting that, stretched to the limit of its tether,the claim could be reduced to a question, "no less ra-dical than . .. do the people of the United States form a NATION?" Wilson's analysis of the issues is shaip but truncated, erudite and somewhat digressive, hut relentless in the logic of constitutionalism itself Before considering the main points he establi-shes with clarity and authority, it is of interest to identify the principal source of his broad philosophical perspective. His own words leave no doubt:

I am, first, to examine this question by the principles of general jurisprudence. What I shall say upon this head, I introduce by the observation of an original and profound writer, who, in the philosophy of mind, and all the sciences attendant on this prime one, has formed an area not less remarkable,and far more illustrious,than that formed by the justly celebrated Bacon,in another science,not prosecuted with less ability, but less dignified as to its object;I mean the philosophy of matter.Dr. Reid,in his excellent enquiry into the human mind, on the principles of common sense, speaking of the skeptical and illiberal philosophy, which under bold, but false, pretentions ... [prevai-ling] in many parts of Europe before he wrote, makes the following judicious remark: 'The language of philosophers, with regard to the original faculties of the mind, is so adapted to the prevailing system,that it cannot fit any other;like a coat that fits the man for whom it was made,and shews him to advantage, which yet will fit very awkward upon one of a different make,although as handsome and well proportioned.It is hard-ly possible to make any innovation in our philosophy concerning the mind and its operations, without using new words and phrases, or giving a different meaning to those that are received.'' 11

As he dissects the argument advanced by the State of Georgia, Wilson pauses to make the utterly "Reidian" distinction between natural and artificial terms,the former referring to entities having real existence, the latter to abstract entities of uncertain ontology.'^ Thus, "To the Constitution of the United States the term SOVEREIGN, is totally unknown."

If issues such as that brought before the Court are to be settled, the terms on which they depend must be understood. In the extant case, the relevant terms are 'State' and 'Sovereign',and the nub of the issue is to be found at the point of origin of each. As for the State, says Wilson:

States and Governments were made for man; and, at the same time, how true it is, that his creatures and servants have first deceived,next vilised,and,at last oppressed their master and maker. MAN, fearfully and wonderfully made,is the workmanship of his all perfect CREATOR: A State; useful and valuable as the contrivance is, is the inferior contrivance of man; and from his native dignity derives all its acquired importance.

As to the actual nature of the State, James Wilson's definition might well serve as a dictionary entry.

By a State I mean, a complete body of free persons united together for their common benefit, to enjoy peaceably what is their own, and to do justice to others. It is an artifi-cial person. It has its affairs and its interests: It has its rules: It has its rights: And it has its obligations. It may acquire property distinct from that of its members: It may incur debts to be discharged out of the public stock, not out of the private fortunes of indivi-duals. It may be bound by contracts;and for damages arising from the breach of those contracts.In all our contemplations,however,concerning this feigned and artificial per- son, we should never forget,that, in truth and nature, those, who think and speak, and act,are men. One begins now to follow the arc of the argument. Georgia is an artificial person, hut it exists in virtue of the actual persons constituting the State. If one citizen of Georgia can bring an action against another, then presumably one citizen of Geor-gia might bring an action against two citizens or all citizens; that is, an action against Georgia. Next, Wilson addresses the more basic question of the grounds on which any citizen would resolve to settle disputes in such a way and concludes: The only reason, I believe,why a free man is bound by human laws, is, that he binds himself.

Upon the same principles, upon which he becomes bound by the laws, he becomes amenable to the Courts of Justice which are formed and authorized by those laws. If one free man,an original sovereign, may do all this; why may not an aggregate of free men, a collection of original sovereigns, do this likewise? If the dignity of each singly is undiminished; the dignity of all jointly must be unimpaired. Thus understood, the State is an artificial party to agreements but bound in just the way the collective of ac-tual persons are, for the State is just such a collective. And ,in the event the State dis-honestly violates the terms of an agreement, it scarcely has as a defense the arrogant claim that,in such matters,it is sovereign] The claim itself would call for authentication and close examination of the sources of the sovereignty. As Wilson notes, in other contexts the term has a correlative - that of Subject; the Sovereign has sovereignty over subjects. But the U.S.Constitution reserves no such category. It refers to citizens of the United States. As Georgia can have no sovereignty over those comprising the State of Georgia, it can have no sovereignty over citizens of another state.

Reaching the heart of the matter, James Wilson goes on to sketch the medieval sour-ces of regal prerogatives, this history having no place within the New World. He sum-marizes Blackstone's rather inventive argument for the superiority of the Crown to any jurisdiction beyond itself, an argument agreeable to what Wilson calls "systema-tic despotism." Then, with an acute and prescient comprehension, Wilson identifies two radically different conceptions of the rule of law. Blackstone is defender of one of these; that which decades later would be called the command theory of law and serve as the linchpin of Legal Positivism. Against this, Wilson cites,

... another principle, very different in its nature and operations [forming] in my judg-ment, the basis of sound and genuine jurisprudence; laws derived from the pure source of equality and justice must be founded on the CONSENT of those, whose obedience they require. The Sovereign, when traced to his source, must be found in the man (emphasis added).

Traced to his source, the sovereign is found in the man.

From this point onward,Wilson has little difficulty conveying the grounds on which the claims of Georgia are simply based on a mistake at once historical and conceptual. It was actual persons who consented to be governed by those constitutional principles that required ratification. They had seen fit to form a union under these principles. It was, then, by way of their consent that Georgia itself would exist as a State. The Con-stitution introduces to readers the body to which it owes its authority. It names the bo-dy: "The PEOPLE ofthe United States." These citizens of the origi-nal thirteen, "in or-der to form a more perfect union," established the Constitution.Wilson concludes," By that Constitution Legislative power is vested. Executive power is vested. Judicial power is vested."

Returning now to John Adams's question to Jefferson — whether Jefferson knows Dugald Stewart — Jefferson's answer on March 14, 1820 is revealing:

Dear Sir,A continuation of poor health makes me an irregular correspondent. ... It was after you left Europe that Dugald Stuart. .. and L[o]rd Dare . . . came to Paris ... Stuart is a great man, and among the most honest living ... I consider him and Tracy as the ablest Metaphysicians living; by which I mean Investigators of the thin-king faculty of man. Stuart seems to have given it's natural history, fi'om facts and observations; Tracy it's modes of action and education, which he calls Logic and Ide-ology; and Cabanis, in his Physique et Morale de l'homme, has investigated anato-mically, and most in-geniously, the particular organs in the human structure which may most probably exercise that faculty.13

This reply is interesting in several different respects.First,it identifies the philosophers Jefferson judges to be the proper leaders of thought. Destutt Tracy and Maine de Bi-ran were the leaders of the school ofldeologie which conferred ultimate epistemolo-gical authority on experience itself. Cabanis's Essai on the relationship between the physical and the mental was an uncompromisingly physiealistic theory of mind, em-bracing not only thought and feeling but creativity,the arts,and the civic dimensions of life. Cabanis would thus he in the same school of thought dominated in the English-speaking world by Joseph Priestley; the Priestley who had declared him-self David Hartley's disciple. Hartley's landmark Observations on Man (1748) was a systematic application of Newtonian principles to a mental science now recast as an essentially physiological science. Predictably, Jefferson was won over to this perspective, as was Benjamin Rush. Adams, so admiring of Reid, knew enough to conclude that the excitement here was as doomed to be disappointed as was the project of human perfection itself.

In a fine recent study of Hartley, Richard Allen makes the suggestive claim that, in the years surrounding the American Revolution, the principle options available to the in-tellectual community were those presented hy Reid and by Hartley.'" Priestley's tho-rough commitment to Hartley's psychology, combined with Priestley's own influential position within the intellectual lif of the New World, fills out the Hartleian project. It is rigorously scientific, reductionistic, promissory. It moves the causal forces operating on human endeavors to the relatively inaccessible and even dark recesses of nerve and hrain and biology. It would govern mental life with laws of association over which the thinker has no direct control.

On the other side, the side which Adams and many other leaders of thought found sensible and practical, there was the Reidian philosophy, faithful to the science of Newton but judging that science to proceed not from theory but from observation; a science not of causes but of laws and principles. It was by way of this influence, the diffiise influence of Scottish thought,including the useful if often irksome skepticism of Hume, that the Founders resisted metaphysical extremes and the extremes of action they often encourage.This same influence protected the colonial consumer from most of the products still minted in Europe's frippery shops. A balance was sought and even found between the speculative and the practical, between lofty and sincerely held principles and the dangerous business of genuine self-govemance. No one figure among the Founders established a perfect balance within his own judgments, but as a collective, willingly or grudgingly accessible to the refinements and chaste-nings of close intellectual combat,the Founders produced something remarkable and original:A means by which a "fallen creature" might set about to achieve decent ends with the aid of a govemment designed intentionally to hold at bay its several powerftil branches. If the prevailing tensions could be reduced to personali-ties, and these fur-ther reduced to a few words, perhaps an encounter between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton is sufficiently "textured" for the purpose. Recall the famous visit Hamilton paid to Jefferson,asking him to identify the subjects in the portraits adorning the walls. These were portraits of Newton, Locke,and Bacon, who were,in Jefferson's words,"my trinity of the three greatest men the world has ever produced". At this Ha-milton paused, and then said "the greatest man that ever lived was Julius Caesar." 5 Daniel N. Robinson University of Oxford

NOTES

1. The Adams-Jefferson Letters. Lester Cappon, ed. (Chapel Hill, NC- University of North Carolina Press, 1959), pp. 560-61.

2. An insightful discussion of this history is Douglas Sloan, The Scottish Enlighten-ment and the American College Ideal. (New York: Columbia University Teachers College,

3. Thomas Jefferson,"Autobiography," in The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (20 vols.). A. A. Lopscomb and E. E. Bergh, eds. (1904-1905). (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Society), vol. 1, pp. 3-4.

4. John Witherspoon, A Princeton Companion. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

5. Quotedi in C.A. Briggs, American Presbyterianism. (New York: Charles Scribner's &Sons, 1885), p. 351.

6. In a letter to Adams dated August 14,1809,Rush recalls a letter from J. Cheet-ham, then preparing a life of Paine and inquiring as to the circumstances surroun-ding the writing of Common Sense.Rush tells Adams that he replied,"that Mr. Paine wrote that pamphlet at my suggestion and that I gave it its name." The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush 1805-1813. John Schutz and Douglass Adair, eds. (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1966), p. 164.

7. David Fordyce, The Elements of Moral Phitosophy [1754]. David Kennedy, ed. (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2003), p. 89.

8. Ibid., p. 106.

9. The full text of the Ratification Speech is available in HTML format on the website of the Constitution Society, located via "James Wilson ratification speech."

10. Chisolm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. Dallas 419.

11. Ibid. Numbers in its bold face refer to the pagination in the original.

12. Reid's distinction between natural and artificial language is developed in Sec. II, Ch.4 of an Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense [1964]. Derek Brookes ed. (University Park,PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997).

13. Adams-Jefferson (cited in n. 1, above), pp. 561-62.

14. Richard Allen,David Hartley on Human Nature.(Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1999), p. 1.

15. The Spur of Fame (cited in n. 6, above), p. 2. The account may be apocryphal.

Tietellinen vallankumous neurofysiologiassa:

http://www.nature.com/news/neuroscience-map-the-other-brain-1.13654

Maybe R. Douglas Fields is not Presbyterian, but he has proved their "soul theory"...

Kommentit