Unkarissa esiintyy myös piirejä, joissa kiistetään koko "suomiteoria" jonkinlaisena poliittisena "europuoskaritieteenä" juuri sumeri-unkari-(turaani-)hypotesin hyväksi:

THE CONTROVERSY ON THE ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE HUNGARIANS

© Copyright HUNMAGYAR.ORG

CONTENTS

Introduction

I. The traditional account of Hungarian origins and early history acco...

II. The Finno-Ugrian theory

III. The Sumerian question

IV. The Settlement of the Carpathian Basin and the Establishment of the...

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

This study provides an overview of the principal theories about the origins and early history of the Hungarians,with the objective of determining a scientifically acceptable alternative orientation in a field which has been dominated for the past 150 years by political and ideological interests. The purpose of this study is therefore to outline a more objective perspective by examining the principal research orientations regar- ding the origins and early history of the Hungarians. The historical period in question covers the time span from the first Neolithic settlement of the Carpathian Basin (5000 BC) to the Christianization of Hungary which began around 1000 AD.

What is it exactly that is being celebrated on the occasion of the 1100th anniversary of Hungary's founding in 896 AD? Is it Árpád's "pagan" Hungary or king István's (Stephen) Christian Hungary? Opinions differ greatly on this complex question. In general, contemporary Hungarian historiography seems to be concentrating more on the last 1000 years of Hungarian history from a predominantly Western point of view, thereby artificially restricting Hungarian history and isolating it from its pre-Christian historical and cultural roots which are often misrepresented or ignored. Hungarian history needs to be reassessed in a broader and more balanced perspective.

The principal opposing views are, on the one hand, the traditional account of Hunga- rian origins rooted in the pre-Christian era, which shows a remarkable degree of compatibility with the Sumerian-Hungarian relationship demonstrated by internatio-nal ori-entalist research starting in the first half of the 19th c., and, on the other hand, the more recent Finno-Ugrian theory which was essentially the product of foreign re-gimes in Hungary:Habsburg in the 19th c., and communist in the 20th c. The traditio-nal account of Hungarian origins states that the Magyars and the Huns were identi-cal and traces their roots back to Ancient Mesopotamia. Sumerian-Hungarian ethno-linguistic research seems to confirm this.The Finno-Ugrian theory has sought to con- tradict the traditional account of Hungarian origins and the Sumerian-Hungarian rela-tionship through a seemingly scientific linguistic approach. However, a more careful analysis of the facts reveals that the methodology of the Finno-Ugrian school is unscientific and that the motives of the Finno-Ugrian theory's promoters are political and ideologi-cal: their objective has been to weaken the Hungarian national identity by instilling a collective inferiority complex in order to weaken national resistance and to consolidate foreign rule in Hungary. The current "mainstream" Hungarian historio- graphy ad-heres to the Finno-Ugrian orientation, promoting the view that the Hunga-rians were "primitive Asiatic latecomers and intruders" in the more "civilized" Europe. This official historical interpretation is therefore characterized by a dogmatic state of denial which deliberately ignores or dismisses the ancient Turanian origins of the Hungarians, the Sumerian-Scythian-Hun-Avar-Magyar identity and continuity, and the fundamental cultural, political and military Hungarian achievements of the millenia prior to 1000 AD which laid the foundations of the Hungarian state.

I. THE TRADITIONAL ACCOUNT OF HUNGARIAN ORIGINS AND EARLY HISTORY ACCORDING TO ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL SOURCES

The medieval Hungarian sources refer to the story of the Biblical Nimrod, son of Kush, and Eneth, whose two sons,Hunor and Magor, led the Huns and the Magyars from the regions neighbouring Persia to the land known as Scythia - a designation generally given to the region stretching from the Carpathians into Central Asia (1). From Scythia, first the Huns (5th c. AD), then Árpád's Magyars (895-896 AD) estab-lished themselves in the Carpathian Basin. It is also stated in these sources that Ár-pád was a descendent of Atilla, and that therefore,under Árpád's leadership, the Ma- gyars reconquered Hungary as their rightful inheritance from their Hun forebears (2).

The contemporary Persian, Armenian, Arab, Greek, Russian and Western sources generally concur with the Caucasian-Caspian origin of the Magyars and with the Scythian-Hun-Avar-Magyar identity (3). It is also interesting to note that although the Byzantine sources generally referred to the Magyars as "Turks" (Turkoi), they also mention that by their own account, the Magyars' previously known name which they used themselves was, in Greek translation, "Sabartoi asphaloi" (4). This is extremely important because this name refers to the Sabir people, also known as the Suba-reans, who inhabited the land known by the Babylonians and Assyrians as Subartu which was situated in the Transcaucasian-Northern Mesopotamian-Western Iranian region (5). By their own account, the Sumerians of Southern Mesopotamia also came from this region which they referred to as Subir-Ki (6).

The Hun-Magyar relationship is also referred to in the recently published Hungarian translation of a Turkish version of the history of Hungary, (Tarihi Üngürüsz), based on an earlier Latin text lost during the Turkish wars (16th-17th c.). This source also mentions that when the Huns and the Magyars arrived in Hungary, they both found peoples already settled there who spoke the same language as themselves, thus lending support to the Hun-Magyar identity and extending the continuity of the Hungarian people in the Carpathian Basin further back in time (7).

The traditional account of Hungarian origins and early history was generally accep-ted until the middle of the 19th c. However, since then, the credibility of this account has been questioned. It was argued that the ancient and medieval sources did not stand up to modern "scientific method and evidence".Nevertheless,it should be taken into consideration that the medieval Hungarian chronicles were most likely based upon earlier sources which have been destroyed or lost during the forced Christiani-zation of Hungary and during the subsequent foreign invasions, and that the stories told in the original sources, like many historical myths and legends transmitted by folklore, are often based on real historical facts.(Back)

II. THE FINNO-UGRIAN THEORY

The Finno-Ugrian theory's origins can be traced back to a book published in 1770 by a Hungarian Jesuit, János Sajnovics, in which he claimed that the Hungarian lan-guage is identical to that of the Lapps (8). This work had no immediate significant impact in Hungary, but it was followed up by mainly German linguists, among whom August von Schlözer played the leading role in the development of the Finno-Ugrian linguistic school (9). This school had a determining influence on the development of linguistic research in Hungary during the second half of the 19th c., where linguists of German origin also played a leading role (10). At that time,Hungary was ruled by the Habsburgs, and German influence was very strong in the political, economic, social, and cultural fields.

It is also important to note that the 19th c. saw the rise of modern nationalism throughout Europe, and that German nationalism was among the most chauvinistic. It was in this context that the idea of a superior Aryan race was conceived. Although the term "Aryan race" is no longer considered politically correct and has been replaced by the more scientifically-sounding "Indo-European" term, the fundamental assumption of this ethno-linguistic group's cultural pre-eminence is still being main-tained today (11). Just as the proponents of this theory sought to prove their claims of Indo-European (Aryan) cultural superiority, they also sought to prove that, conver-sely, non-Indo-Europeans were culturally inferior. The Finno-Ugrian theory was therefore promoted in this ideologically biased context (12).

Following the defeat of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848-49, the repres- sive Habsburg regime took over the Hungarian academic institutions and imposed the exclusive research orientation of the Finno-Ugrian theory about the origin of the Hungarians (13). Thus,the Hungarian Academy of Sciences became an instrument of the Habsburg regime's cultural policy of Germanization, which sought to weaken the Hungarian national identity - thereby facilitating foreign domination - through the dis-tortion and falsification of information relating to the origin,history, culture, and langu- age of the Hungarians, censoring and prohibiting any publication or research which did not conform to the officially imposed Finno-Ugrian theory.This was also the case under the Hungarian Communist regime which also pursued an anti-Hungarian policy with the objective of Russification. It was therefore in the interest of these re-gimes to "let the conquered Hungarians believe that they have an ancestry more pri-mitive than that of the Indo-European peoples.In Habsburg times Hungarian children were taught that most of their civilization came from the Germans: today they are taught that their 'barbaric' ancestors were civilized by the educated Slavs" (14).

The Finno-Ugrian theory proved to be most suitable for this purpose. This theory claims that the Hungarians originated from primitive Siberian hunter-gatherer no-mads who wandered Westward and who acquired a higher culture upon coming into contact with Indo-Europeans and other peoples (15). This theory has been increa-singly brought under criticism by dissident and exiled Hungarian researchers be-cause of its negative portrayal of the Hungarians in relation to their neighbours, be-cause of the historical and political circumstances under which this theory has been imposed and perpetuated, and because this theory fails to take into consideration a substan-tial amount of scientific data which contradicts it (16). It should also be noted that according to the scientific review "Nature" (20/02/92), the quality of the research conducted at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences is rather poor,and this also seems to apply to the Finno-Ugrian research orientation.

The Finno-Ugrian theory is based on the hypothetical family-tree model and chrono- logy of the Indo-European ethno-linguistic group's evolution (17).The family-tree mo- del assumes that the members of a defined ethno-linguistic group originated from a common ancestral people which spoke a common ancestral language and lived in a common ancestral homeland from which various groups migrated to form the distinct branches of an ethno-linguistic family. Thus,the Finno-Ugrian theory states that the Finno-Ugrian group separated from the ancestral Uralic group between 5000 and 4000 BC; between 3000 and 2000 BC the Finnic and Ugrian branches separated, and around 1000 BC the "proto-Hungarians" separated from the "Ob-Ugrians" and migrated Westward (18).However,the validity of this monolithic family-tree model has been increasingly questioned by several researchers, including some Indo-European scholars (19).

Although this hypothetical process was supposed to have taken place in the Ural re- gion, the exact location of the various "ancestral homelands" occupied by the various branches and the chronology of these events are still subject to various interpreta-tions as there is no unanimous agreement among Finno-Ugrian scholars themselves (20). The significant degree of uncertainty and confusion which still exists within this field of research is due to the fact that the Finno-Ugrian theory is essentially based on linguistic speculation which is not supported by any conclusive archeological, anthropological and historical evidence (21). In fact,most of the available evidence seems to contradict the Finno-Ugrian theory,and furthermore,serious reservations have been raised concerning some of its linguistic arguments (22). Several resear-chers have also pointed out that the Finno-Ugrian theory contains serious methodo-logical incon-sistencies and errors, that the term "Finno-Ugrian" itself is arbitrary and unscientific, and that the inclusion of Hungarian in the Uralic group is artificial and without adequate scientific basis (23).

It is not the apparent linguistic similarities between the Hungarian and the Uralic lan- guages which are in question, but the nature and degree of the relationship between the two groups. The Finno-Ugrian theory's assumption that the Hungarians are di-rectly descended from the "Finno-Ugrians" and that the Uralic peoples are the only ethno-linguistic relatives of the Hungarians seems to be fundamentally flawed:a spe-cific linguistic relationship does not necessarily correspond to a genetic relationship, nor can it exclude relationships with other ethnic groups. The Finno-Ugrian theory rejects the possibility that the Uralic group may somehow be related to other ethno-linguistic groups such as the Altaic group (24), perhaps partly because the first major challenge to the Finno-Ugrian theory came from advocates of the theory that the Hungarians were of Turkic origin, based on the numerous and significant observable linguistic, cultural and anthropological similarities between the Hungarian and Turkic peoples, as well as on historical evidence (25).

In fact, comparative linguistic analysis has shown that there are many similarities be-tween Hungarian and several other major Eurasian ethno-linguistic groups, and al- though the Finno-Ugrian theory claims that these similarities are the results of borro-wings on the part of the Hungarians (26), it nevertheless appears that the Finno-Ug-rian theory requires a fundamental revision concerning the relationship between the Hungarians and the Uralic group, as well as their relationship to other ethno-linguis-tic groups. An alternative explanation for the existing linguistic relationship between Hungarian and other languages,including the Uralic and Altaic languages,is provided by the Sumerian ethno-linguistic and cultural diffusion theory, according to which the Eurasian ethno-linguistic groups were formed under the dominant cultural and lin-guistic influence of the Sumerian-related peoples originating from the Near East and which have progressively spread throughout Eurasia during several millenia since the Neolithic period (5000 BC). (Back)

III. THE SUMERIAN QUESTION

After British, French and German archeologists and linguists discovered and deci-phered the oldest known written records in Mesopotamia and its neighbouring re-gions during the first half of the 19th c., they came to the conclusion that the lan-guage of those ancient inscriptions was neither Indo-European nor Semitic, but an agglutinative language which demonstrated significant similarities with the group of agglutinative languages known at the time as the Turanian ethno-linguistic group which included Hungarian, Turkic,Mongolian and Finnic (later referred to as the Ural-Altaic group) (27).

The recognition and acceptance of the Sumerian-Turanian ethno-linguistic relation- ship grew significantly in international orientalist circles until the 1870's (28). How-ever, two factors hampered the further progress of research in this field.First, in Hun-gary, as a result of the imposition of the Finno-Ugrian theory as official doctrine follo-wing the 1848-49 War of Independence,all research concerning the Sumerian ques-tion was discouraged and this official attitude still prevails today in Hungary (29).

The second factor which had a considerable impact on the international level was the promotion of the theory that the Sumerians had never existed and that their lan-guage was invented by the Semitic priests of Babylonia as a means of secret com-munication (30). This theory was devised by J. Halevy, a rabbi from Bucharest who had obtained a position at the Sorbonne. This radical theory, despite its numerous flaws and obvious ideological motive, had a divisive effect among orientalists and broke the momentum gained by the advocates of the Sumerian-Turanian relation-ship. Since then,the Sumerian question seems to have been relegated to a minor status and passed under silence, the Sumerians having been generally dismissed as an isolated ethno-linguistic group of unknown origin having no known affinities with modern ethno-linguistic groups (31).

The silence was broken after WWII by Hungarian expatriates in the West who redis-covered the Sumerian question as they were able to gain access to the original Western sources of documentation on the Sumerians. These Hungarian researchers accumulated a considerable amount of evidence in support of the theory that the Sumerian and Hungarian languages are related.The reaction from official academic circles in Communist Hungary was that of categorical dismissal and discrediting of the Hungarian expatriate researchers, claiming that they were not competent in the field of Sumerology and that they were ideologically motivated. However, to this day, no conclusive evidence has been provided by official Hungarian academic circles to prove their claims regarding the Sumerian question and the origin of the Hungarians, as they simply refuse to examine the question in an open, rational and scientific manner. This attitude seems to be ideologically motivated (32).

The principal arguments against the Sumerian-Hungarian relationship appear to be unfounded: first, the apparent ambiguity arising from the polyphonic and polyseman- tic character of Mesopotamian cuneiform written symbols, which would render uncer- tain the decipherment of the ancient texts and the identification of their language. This apparent confusion is the result of the fact that the Semitic peoples which settled in Sumerian Mesopotamia (from 2340 BC) adopted the Sumerian writing sys-tem, but reassigned new phonetic and semantic values to the Sumerian cuneiform characters (33).This was clearly shown by the multilingual inscriptions which included syllabaries and dictionaries explaining the Sumerian and Semitic phonetic and semantic values of the characters (34).

Also,the intermingling of the Sumerian and Semitic populations of Mesopotamia was reflected in the evolution of the Sumerian language (35).However,it would be mislea- ding to compare the resultant hybridized Mesopotamian dialects to the Hungarian language since this would apparently weaken the Sumerian-Hungarian linguistic cor-relation. Thus, it should be taken into account that the Sumerians had existed in Me-sopotamia for several thousand years prior to the arrival of the Semitic peoples, and that during this period, several regional dialects had evolved (36). Another factor which should be considered by linguists is the fact that the Hungarian language has been somewhat modified since the 19th c., and that as a result, some of the more archaic forms of Hungarian which have shown a definite relationship to Sumerian are no longer used in modern Hungarian. It seems therefore that in order to obtain more accurate results in comparative Hungarian-Sumerian linguistic analysis, it is the most archaic forms of these two languages which should be compared.

The principal results of the research conducted so far on the Sumerian-Hungarian relationship have indicated that these languages have over a thousand common word roots and a very similar grammatical structure (37). In his Sumerian Etymologi-cal Dictionary and Comparative Grammar, Kálmán Gosztony, professor of Sumerian philology at the Sorbonne, demonstrated that the grammatical structure of the Hun-garian language is the closest to that of the Sumerian language: out of the 53 cha-racteristics of Sumerian grammar, there are 51 matching characteristics in the Hun-garian language,29 in the Turkic languages,24 in the Caucasian languages,21 in the Uralic languages, 5 in the Semitic languages,and 4 in the Indo-European languages.

The linguistic similarities between Sumerian,Hungarian and other languages are cor- roborated by the archeological and anthropological data discovered so far. These ar- cheological finds indicate that the Sumerians were the first settlers of Southern Me-sopotamia (5000 BC), where they had come from the mountainous regions to the North and East with their knowledge of agriculture and metallurgy, and where they built the first cities.Increased food production through the use of irrigation allowed an unprecedented population increase, resulting in successive migratory waves which can be traced archeologically and anthropologically throughout Eurasia and North Africa (38). Thus, from the evidence left by this process of colonization, it appears that the Sumerian city-states were able to exert a preponderant economic, cultural, linguistic and ethnic influence during several thousand years not only in Mesopota-mia and the rest of the Near East,but also beyond,in the Mediterranean Basin, in the Danubian Basin, in the regions North of the Caucasus and of the Black Sea, in the Caspian-Aral, Volga-Ural, and Altai regions, as well as in Iran and India. It seems therefore that the Sumerians and their civilization had a determining influence not only on later Near-Eastern civilizations, but also on the Mediterranean, Indian, and even Chinese civili-zations, as well as on the formation of the various Eurasian ethno-linguistic groups (39).

One of the most comprehensive studies examining this complex question is László Götz's 5-volume 1100-page research work entitled "Keleten Kél a Nap" (The Sun ri-ses in the East),for which the author consulted over 500 bibliographical sources from among the most authoritative experts in the fields of ancient history, archeology, and linguistics. In his wide-ranging study, László Götz examined the development of the Sumerian civilization, the determining cultural and ethno-linguistic influence of the Near-Eastern Neolithic, Copper and Bronze Age civilizations upon the cultural deve- lopment of Western Eurasia, and the linguistic parallels between the Indo-European, Semitic and Sumerian languages indicating that the Sumerian language had a con-siderable impact on the development of the Indo-European and Semitic languages which have numerous words of Sumerian origin.László Götz also examined the fun-damental methodological shortcomings of Indo-European and Finno-Ugrian ethno-linguistic research. His conclusion is that most Eurasian ethno-linguistic groups are related to one another in varying degrees, and that these groups, such as the Indo-European, Uralic and Altaic groups, were formed in a complex process of multiple ethno-linguistic hybridization in which Sumerian-related peoples (Subareans, Hur-rians, Kassites, Elamites, Chaldeans, Medes, Parthians) played a fundamental role. Other researchers seem to have come to similar conclusions:

"The Indo-Europeanization of Europe did not mean total destruction of the pre- vious cultural achievement but consistedin an amalgamation (hybridization) of ra- cial and cultural phenomena. Linguistically, the process may (and must) be regar- ded in a similar way:the Indo-Europeans imposed an idiom which itself then adop- ted certain elements from the autochtonous languages spoken previously. These non-Indo-European (pre-I-E) elements are numerous in Greek,Latin, and arguab-ly, Thracian... the Thracians were highly conservative in their idea of urbanism; their language reflects this reality in terms (words, place-names) the origin of which can be traced back to the idioms spoken in the Neolithic (pre-I-E) times... The Romanian name for Transylvania, Ardeal, is one of the clearest pre-I-E relics ... place-names are of great importance in the reconstruction of vanished civiliza-tions and it is almost inevitable that the identifiable pre-I-E elements come down from the Neolithic times:the dawn of the European civilization... the terms implying complex societies are of pre-Indo-European origin." (40)

Thus, it appears that the ancient pre-Indo-European peoples which settled in Europe were, for the most part, of Sumerian-related Near Eastern origins,and were later de- signated as the pre-Hellenic Aegean peoples,the Thracians,the Dacians,the Illyrians, the Etruscans, the Iberians,the Cimmerians and the Sarmatians. These peoples laid the foundations of European civilization and later intermingled with various other peoples to form the ethnic groups which are currently referred to as "Indo-Euro-pean". There are,however,certain ethno-linguistic groups which have withstood this process of "Indo-Europeanization", and which have therefore preserved their non-Indo-Euro-pean identity, such as the Basques, the Finnic peoples, and the Carpa-thian basin's indigenous population (the Neolithic, Copper and Bronze Age settlers) (41). The archeological and anthropological finds of the Carpathian Basin indicate that this indigenous population was related to, and at least in part originated from the ancient pre-Semitic Near-Eastern cultures (42). The same seems to apply to the Scythian, Hun, Avar, Magyar, Khazar (Sabir),Bulgar,Cuman and Petcheneg peoples of Eastern Europe and Central Asia which settled in Central Europe, including the Carpathian Basin.

IV. THE MAGYAR CONQUEST OF THE CARPATHIAN BASIN AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE HUNGARIAN STATE BY ÁRPÁD

The different views of the facts relating to the Magyar conquest and settlement of the Carpathian Basin and to the foundation of the Hungarian state are highly polarized between non-Hungarians and Hungarians, as well as among Hungarians them-selves. The opposing views manifest themselves around the questions of the cultu-ral level of the Magyar tribes,the circumstances of their arrival in the Carpathian Ba-sin,the ethnic identity of the previously settled inhabitants of that region,and the role of Western political and religious influence in the formation of the Hungarian state.

Whereas the mainstream claims that the Magyar tribes were "primitive Asiatic bar-barians" swept Westward by a great migratory wave and which were forced to settle in the Carpathian Basin as their "plundering raids" against the West were halted by "superior force", following which their cultural level was "somewhat raised" by the "benficial influence" of "European civilization", the opposing traditionalist view holds that the Magyars had in fact a highly developed material and spiritual culture, and a well organized society, that their settlement of the Carpathian Basin was a skillfully planned and executed military and political undertaking,that their military campaigns against the West had a well defined strategic objective, and that the West did not have the political-ideological cohesion necessary to destroy the Hungarians.

Another contentious issue is that of the ethnic identity of the populations which inha- bited the Carpathian Basin at the time of the Magyar Conquest.One side claims that this region was already inhabited by Slavic,"Daco-Roman", Germanic and other non- Hungarian peoples which were oppressed by the "invading" Magyars. The opposing view argues that the majority of the population already established in the Carpathian Basin was in fact ethnically related to the Magyars, and that today's Hungarians are an amalgamation of these peoples whose settlement of the Carpathian Basin preceded that of the non-Hungarian ethnic groups currently settled there.

An increasingly divisive issue among Hungarians is that of the role of Western politi- cal and religious influence in the formation of the Hungarian state. One side claims that the adoption of the European feudal political system and of Western Christia-nism resulting in Hungary's integration to the West was of "great cultural benefit" and represented a "higher level of civilization" compared to the previous tribal federation of the "pagan" Magyars.The opposing view holds that the forced integration to the West had highly detrimental consequences for Hungary, and that the imposition of Christianism and of the feudal system served foreign interests hostile to Hungary. This view also holds that Árpád was the founder of the Hungarian state, and not king István who is seen as the instrument of a foreign-backed coup which led to a radical change in the political and ideological orientation of Hungary.

The conflicting interpretations of the events leading up to and following the Magyar settlement of the Carpathian Basin in 895-896 AD indicate the necessity of re-exami- ning the established official version. The generally propagated version of the events surrounding the Magyar settlement states that after having been subjects of the Khazar empire, the Magyar tribes were forced to flee Westward due to their defeat by the advancing Petchenegs (43), thus arriving in the Carpathian Basin where they subju- gated the already established populations which were supposedly Indo-Euro-pean (44). After the conquest, the Magyar tribes conducted raids against Western Europe which were stopped as a result of their defeat by the Germans in 955, following which the Magyars remained in Hungary and were converted to Western Christianism.

...

CONCLUSION

It appears therefore that a fundamental revision of early Hungarian history is neces- sary in order to arrive at a more accurate picture, and much research work remains to be done in this field. Based on the available information, it seems most probable that the Hungarians are a synthesis of the peoples which have settled in the Carpa-thian Basin since the Neolithic period up to the Middle Ages:the Sumerian-related peoples of Near-Eastern origin (Neolithic, Copper and Bronze Ages), followed by the Scythians (6th c. BC), the Huns (5th c. AD), the Avars (6th c.), the Magyars (9th c.), the Petchenegs (11th c.),and the Cumans (13th c.). This Hungarian synthesis is cha-racterized by a remarkable ethno-linguistic homogeneity and has remained highly differentiated from the considerably more numerous surrounding Indo-European peoples. The conclusion which can be drawn from this is that the Hungarians were able to preserve their ethno-linguistic identity and to maintain a demographic majori-ty or criti-cal mass within the Carpathian Basin as a result of the periodical inflow of ethno-linguistically related peoples. These peoples were designated in the 19th c. as Turanians, and the Sumerians, Scythians, Huns, Avars and Magyars were all considered to belong to this ethno-linguistic group.

Presently there are still many misconceptions concerning the Turanian peoples: it is still widely believed, erroneously, that the Scythians were an Indo-European people, that the Huns and Avars were Turkic-speaking peoples of Mongolian race or origin, and that the Magyars were a mixture of Finnic and Turkic elements. These miscon-ceptions originate from an inaccurate historical perspective which failed to recognize the existence of a distinct Turanian entity amidst the multi-ethnic conglomerates of the Scythians, Huns, Avars, and Magyars, whose empires consisted of tribal federa-tions which included various other ethnic groups: Indo-Europeans, as well as Uralic and Altaic peoples besides the dominant Turanian elements. It now seems that this Turanian ethno-linguistic group to which the Hungarians belong was a distinct group from which the Uralic and Altaic ethno-linguistic groups later evolved through a pro- cess of ethno-linguistic diffusion and hybridization. This explanation of the existing ethno-linguistic affinities between the Hungarians and the Uralic and Altaic groups would be more in line with the latest findings on this subject. In light of these findings, it would seem appropriate to re-examine this question objectively, avoiding the offi-cially imposed ideological biases which have clouded the issue since the middle of the 19th c. and still continue to do so today.

Risto Juhani Koivula kommentoi_ 23. heinäkuu 2016 07:16

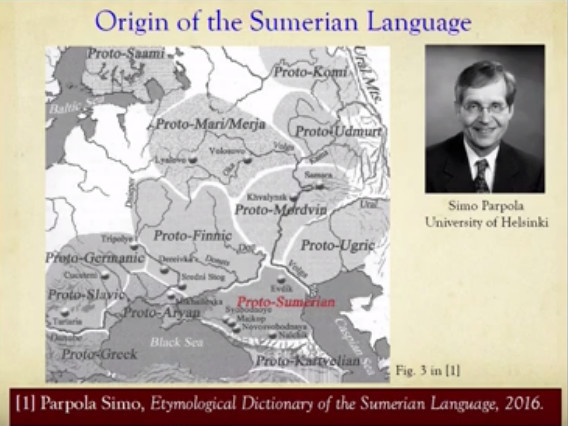

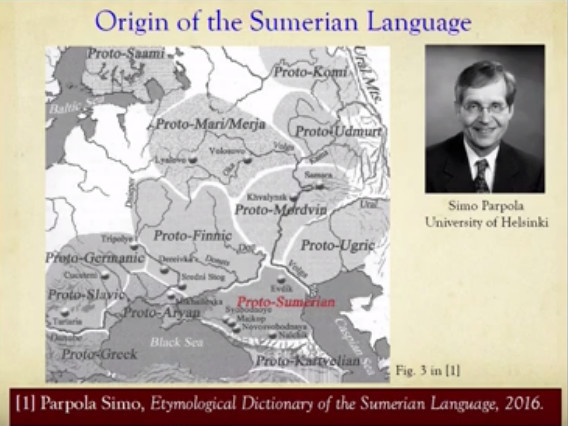

Tässä on Simo Parpolan pelinavausartikkeli sumerista uralilaisen kielikunnan kiele-nä. Keskeinen argumentti on,että monia sanoja ei löydy muualta kuin uralilaisen kie- likunnan suomalaisesta ja urgrilaisesta haarasta ja sumerista. Toinen argumentti on, että nämä ovat mitä keskeisintä sanastoa.

53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Moscow, July 23, 2007

Sumerian: A Uralic Language

Simo Parpola (Helsinki)

In the early days of Assyriology, Sumerian was commonly believed to belong to the Ural-Altaic language phylum. This view originated with three leading Assyriologists, Edward Hincks,Henry Rawlinson and Jules Oppert, and other big names in early As- syriology such as Friedrich Delitzsch supported it (Fig. 1). The Frenchman François Lenormant, who wrote on the subject in 1873-78, found Sumerian most closely rela-ted to Finno-Ugric, while also containing features otherwise attested only in Turkish and other Altaic languages.

The wind turned in the early 1880s,however,as two prominent Finno-Ugrists, August Ahlqvist and Otto Donner, reviewed Lenormant's work and concluded that Sumerian was definitely not a Ural-Altaic language (Fig.2).This was widely considered a death- blow to the Sumerian-Ural-Altaic hypothesis, and since then Assyriologists have ge-nerally rejected it.Typically,when a Hungarian scholar in 1971 tried to reopen the dis-cussion in the journal Current Anthropology, a few linguists welcomed the idea but the reaction of the two Assyriologists consulted was scornfully negative.

Attempts to connect Sumerian with other languages have not been successful, how- ever,and after 157 years,Sumerian still remains linguistically isolated. This being so, there is every reason to take another look at the old Ural-Altaic-hypothesis, for it has never been properly investigated.In the 19th century,Sumerian grammar and lexicon were as yet too imperfectly known to be successfully compared with any languages, while all more recent comparisons suffer from the lack of Assyriological or linguistic expertise and are hence for the most part worthless. This does not mean, however, that they are all garbage:at least 194 of them seem perfectly acceptable both phono-logically and semantically (Fig.3). That is a number large enough to deserve serious attention. Of course, it does not prove that Sumerian was related to Ural-Altaic languages, but it does indicate that the possibility exists and should be carefully re- examined in order to be either substantiated or definitively rejected.

To this end, I started in November 2004 a project called "The Linguistic Relationship between Sumerian and Ural-Altaic",on which I have been working full time since May 2006,with funding from the Academy of Finland.The aim of the project is to systema-tically scrutinize the entire vocabulary of Sumerian with the help of modern etymolo-gical dictionaries and studies, identify all the words and morphemes that can be rea-sonably associated with Uralic or Altaic etyma, ascertain the validity of the compari-sons, convert the material into a database, and make it generally available on the Internet.

The database under construction will contain all the attested phonetic spellings and meanings of the compared Sumerian and Ural-Altaic lexical items,as well as,for con- trol purposes, all Indo-European etymologies proposed for these items. The rele-vance of each comparison is assessed separately for form and meaning on a scale from 4 to 1 (Fig.4). The highest score, 4+4,indicates perfect agreement in form and meaning;a low score correspondingly poor agreement and doubtful relevance. In de- ciding whether a comparison is relevant or not, the governing principle has been that all compared items must match reasonably well in both form and meaning, and any differences in form or meaning must conform with the phonological and semantic variation attested in the languages compared.

To date,I have systematically gone through about 75 per cent of the Sumerian voca- bulary and identified over 1700 words and morphemes that can be reasonably asso- ciated with Uralic and/or Altaic etyma, allowing for regular sound changes and se-mantic shifts. Somewhat surprisingly, words with possible Altaic etymologies consti-tute only a small minority (about seven per cent) of the total, and it is unlikely that the picture will essentially change by the time the project has been finished.

Although a close relationship of Sumerian with the Altaic family as a whole thus seems excluded, a genetic relationship with Turkish seems possible, as most of the matches are with Turkic languages, and they are basic words and grammatical morphemes also found in Uralic languages.

Practically all the compared items are thus Uralic,mostly Finno-Ugric. The majority of them are attested in at least one major branch of Uralic beside Finnic and thus cer- tainly are very old,dating to at least 3000 BC.A large number of the words are known only from Finnic,but this does not prevent them from being ancient as well,since they have no etymology and are for the most part common words attested in all eight Finnic languages.

This collection of words runs the gamut of the Sumerian vocabulary (Fig. 5) and in- cludes 478 common verbs of all possible types, such as verbs of being, bodily pro-cesses, sensory perception, emotion, making,communication, movement etc., adjec-tives, numerals, pronouns, adverbs, interjections, conjunctions, and 589 nouns inclu-ding words for body parts, kinship terms, natural phenomena, animals, plants, wea-pons, tools and implements,and various technical terms reflecting the cultural level of the neo- and chalcolithic periods (in the fields of agriculture, food production, animal husbandry, weaving, metallurgy, building technology, etc.). I would like to emphasize that the majority of the words in question are basic words, and 75 per cent of them show a very good match in form and meaning. This does not mean that they are ne-cessarily all correct,but they stand a very good chance of being so.About 20 per cent of the comparisons are more problematic and about 5 per cent of them are conjectu- ral only. All clearly impossible comparisons will of course be excluded once the material has been thoroughly analysed.

Over 1700 lexical matches with Uralic surely sounds like an awful lot, "too good be true", if compared with all the previous fruitless attempts to find a cognate for Sume- rian. But it is not at all much for genetically related languages;on the contrary, it is what must be legitimately expected of languages that are related.Who marvels at the fact that members of the Indo-European language family, even ones widely separa-ted in time and place, have a large number of words in common? The large number of common words is precisely the reason why these languages can so easily and securely be identified as members of the same family.

It may be asked why all these numerous lexical matches with Uralic have not been found earlier. The explanation is simple. It takes a good knowledge of the Uralic lan- guages plus familiarity with the intricacies of Sumerian phonology and cuneiform wri-ting system to recognize the connections between Sumerian and Uralic, and such a combination of special expertise is rare. Very few Assyriologists know any Uralic lan-guages, and experts in Uralic studies do not know any Sumerian. Of course, beside the required special expertise one would also need the will to study the matter se-riously, and such will has been entirely lacking in Assyriology for the past 120 years.

In order to get a better idea of the relationship between Sumerian and Uralic, let us now have a look at some of the comparisons to see what they are like and how they work in practice.

34 years ago Miguel Civil in his article "From Enki's headache to phonology" showed that late Sumerian ugu,"top of the head", is the same word as earlier a-gü; and from the alternation of a-gü with the divine name dab-ü, he concluded that it probably ori-ginally contained a labiovelar stop in the middle (Fig. 6). Recently, Joan Westenholz and Marcel Sigrist have shown that beside "top of the head",ugu also means "brain." {Hungarian agy= brain} Both formally and semantically,the Sumerian word thus mat-ches the Uralic word *ajkwo "brain, top of the head", which can be reconstructed as containing a labiovelar stop in the middle based on its reflexes in individual Uralic languages.Remarkably,Sumerian ugu4 "to give birth",a homophone of ugu, likewise has a close counterpart in Finnic aiko-,aivo-,"to intend; to give birth". The semantics of the Finnic word show that it derives from the word for "brain",and the alternation of /k/ and /v/ in the stem confirms the reconstruction of the labiovelar in the middle of the word.

Several other words discussed by Civil also display an alternation of /g/ and /b/, including gurux or buru "crow", and gur(u) 21 "shield", also attested as kuru 14, e-bu-ür and (Fig. 7). These two words certainly were almost homophonous, since they could be written with the same logogram. The common Uralic word for "crow", *kwarks,indeed contains the posited labiovelar stop and provides a perfect etymolo- gy for the Sumerian word.The original labiovelar is preserved in Selkup,but has been replaced by /v/ in other Uralic languages except Sayan Samoyed,where it is appears as /b/. Sumerian gur(u)21 "shield" can be compared with Finnic varus "protection," whose original form can be reconstructed as *kwaruks and thus provides a perfect etymology for the Sumerian word.{?Hungarian üv=to protect from harm,vür = a fort}

The regular replacement of the labiovelar by /g/, /k/ or /b/ in Sumerian and by /v/ in Uralic amounts to a phonological rule and helps establish further connections bet- ween Sumerian and Uralic words displaying a similar correlation, for example Sume- rian gíd "to pull" and Uralic *vetä- "to pull," {Hungarian huz t>z} and Sumerian kur "mountain" and Uralic *vor "mountain".{also common as kur in many FU languages} The reconstruction of an original labiovelar in the latter case is strongly supported by Volgaic kurok, "mountain." The phonological correspondences between Sumerian and Uralic remain to be fully charted, but a great many of them certainly are perfectly regular. For example, in word initial position Sumerian /*š/ regularly corresponds to Finnic /h/, while Sumerian /s/ regularly corresponds to Finnic /s/ (Fig. Cool. {In Hungarian its often s, ch, sh }

The word a-gü just discussed was written syllabically with two cuneiform signs,A and KA, both of which have several phonetic values and meanings based on homophony and idea association (Fig. 9). All these phonetic values and meanings have close counterparts in Uralic,and the homophonic and semantic associations between the individual meanings work in Uralic,too;compare the homophony between a,aj "water" and aj,aja "father" in Sumerian, and jää,jäj and äj, äijä in Uralic. And this applies not only to the signs A and KA but,unbelievable as it may sound, practically the whole Sumerian syllabary. Consider, for example, the sign AN (Fig. 10), whose basic mea-ning, "heaven,highest god",was in Old Sumerian homophonous with the third person singular of the verb "to be",am6. The Uralic word for "heaven" and "highest god" was *joma,which likewise was virtually homophonous with the third person singular of the verb "to be", *oma. These two words would have become totally homophonous in Sumerian after the loss of the initial /j/. The loss of the initial /j/ also provided the homophony between Sumerian a "water" and aj "father" just mentioned.

Such a close and systematic parallelism in form and meaning is possible only in lan- guages related to each other.Accordingly,the logical conclusion is that Sumerian is a Uralic language.This conclusion is backed up by the great number of common words and the regularity of the phonological correspondences between Sumerian and Ura-lic already discussed,as well as by many other considerations.Sumerian displays the basic typological features of Uralic;it has vowel harmony,no grammatical gender but an opposition between animate and inanimate, and its grammatical system is clearly Uralic, with similar pronouns,case markers,and personal endings of the verb. In addi-tion, many Uralic derivational morphemes can be identified in Sumerian nouns and verbs.The non-Uralic features of Sumerian,such as the ergative construction and the prefix chains of the verb, can be explained as special developments of Sumerian in an entirely new linguistic environment after its separation from the other Uralic languages.

The Sumerians thus came to Mesopotamia from the north, where the Uralic lan-guage family is located (Fig. 11), and by studying the lexical evidence and the gram-matical features which Sumerian shares with individual Uralic languages, it is pos-sible to make additional inferences about their origins.The closest affinities of Sume-rian with-in the Uralic family are with the Volgaic and Finnic languages, particularly the latter,with which it shares a number of significant phonological,morphological and lexical isoglosses. The latter include, among other things, a common word for "sea, ocean" (Sumerian ab or a-ab-ba, Finnic aava, aappa), and common words for ce-reals, sowing and harvesting, domestic animals,wheeled vehicles,and the harness of draught animals (Fig. 12). A number of these words also have counterparts in Indo-European, particularly Germanic languages. These data taken together suggest that the Sumerians originated in the Pontic-Caspian region between the mouth of the Volga and the Black Sea, north of the Caucasus Mountains, where they had been living a sedentary life in contact with Indo-European tribes. I would not exclude the possibility that their homeland is to be identified with the Majkop culture of the North Caucasus, which flourished between 3700 and 2900 BC and had trade contacts with the late Uruk culture (Fig.13).Placing the Sumerian homeland in this area would help explain the non-Uralic features of Sumerian for the Kartvelian languages spoken just south of it are ergative and have a system of verbal prefixes resembling the Sume-rian one. The Sumerian words for wheel and the harness of draft animals that it shares with Uralic show that its separation from Uralic took place after the invention of wheeled vehicles, which were known in the Majkop culture since about 3500 BC.

About 3500 BC,the Indo-European Yamnaya culture that had emerged between the Danube and the Don began to expand dynamically to the east, reaching the Cauca-sian foreland by about 3300 BC.This expansion is likely to have triggered the Sume- rian migration to Mesopotamia. It would have proceeded through the Caucasus and the Diyala Valley, and since wheeled transport was available,could easily have been completed before the end of the Late Uruk period (c. 3100 BC). The arrival of the Su-merians would thus coincide with the destruction of the Eanna temple precinct at the end of the Uruk IVa period.

The lexical parallels between Sumerian and Uralic thus open up not only completely new possibilities for the study of Sumerian, but also a chance to identify the original homeland of the Sumerians and date their arrival in Mesopotamia. In addition, they provide a medium through which it becomes possible to penetrate into the prehistory of the Finno-Ugric peoples with the help of very ancient linguistic data.Of course, it is clear that the relevant evidence must first pass the test of verification or falsification before any part of it can be generally accepted and exploited.

I am currently preparing an Internet version of the database in collaboration with the Department of General Linguistics of the University of Helsinki. This web version is planned to be interactive and will contain a search engine and a program to check the regularity of the sound changes involved in the comparisons. I heartily invite all sceptics to visit the site once it is ready and falsify as many of the comparisons as they can, and everybody else to look at the evidence, check it out, and contribute to it by constructive criticism and new data.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kv7pauLtUME

Sumerian and Finno-Ugric Regular Sound Changes

Peter Revesz

SIMO PARPOLA: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simo_Parpola

SB: Parpolan *aikwo- ja *gweta- ja *kwar- (sota) -esimerkit ovat erittäin mielenkiin-toisia, ja juuri tuollaisia äänteenmuunnoksia on tapahtunut, MUTTA KIELI EI OLE NIISSÄ KANTAURALI, UROOPPA,"SEN MURRE" KANTABALTTI ja ITÄBALTTI-LAINEN, SUURESTI MUUNTUNUT VASARAKIRVESKIELI, kauempana kantabaltista kuin nykyliettua.

Kantaindoeuroopan *kʷ ja *gʷ -äänteet muutuvat (illmeisesti) varhaisessa kantabal- tissa *kw- ja *gw- -äänteiksi (puolivokaali w) liudentuneet *kʷ´ myös *tw- tai *(t)šw- sekä *gʷ´, *dw- tai *(d)žw-. Usein putoaa jompi kumpi, tai sekä toinen että toinen, pois, ja usein molemmat variantit jatkavat vähän eri merkitykssissä. Itäbaltille tyypillistä on ensimmäisen, oikean konsonantin putoaminen (suomalaiseen tapaan), länsibaltille taas puolivokaalin putoaminen. Puolivokaali voi olla w, l (ł), j, m tai n.

Esimerkkkejä on vaikka kuinka paljon: *kʷer- = hakata, sotia > lt. karas = sota, pr. karja = sotajoukko, sm varus- = sota-, ranskan guerre, engl. war jne. (suomen karja tulee ehkä sanasta *gwarja = maata tömistelevä ja "jauhava" karja(lauma), lt. žergti)

Kanta-IE:*ēkʷe = vedenpinta, vesiaava > aqua, ekva-, Akaa, Oka (joki), aava, aapa jne.

(*G´w´ēna (= valuu, kuin terva, tai laiduntava karja) > *Dwēna (= "Hiljaa virtaa" -joki ) > Don (tietysti; kääntäjä on tiennyt tämän etymologian), Teno, Tonava/Danube, Viena/Dvina, Väinä/Dvina, alun perin kelttiläinen Wien/Vienna; tyyni, vieno, vaiti.

jne.

http://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2014/01/su-ja-balttilaisten-kielten-kehtysyhteyksita-balttilaisen-lahteen-mukaan

http://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2015/02/uralilaisten-ja-kamtshatkalaisten-kielten-yhtalaisyyksia

http://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2011/09/sven-svin-etymologiaa

http://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2015/10/juha-kuisma-ja-hameen-paikannimet-peruslinja-oikea-lempo-luuraa-yksityiskohdissa

Risto Juhani Koivula kommentoi_ 23. heinäkuu 2016 13:45

Tässä eräs KOTUSin palveluksessa oleva Jaakko "Jaska" Häkkinen, pangermanistinen fennougristi, arvostelee tuota samaa Simo Parpolan juttua:

Sumeri ja uralilaiset kielet

Jaska

Seuraa

Viestejä2756

Liittynyt15.9.2006

klo 23:58 | 28.9.2007

Uralilais-sumerilaisesta yhteydestä

Seuraavassa kommentoin Aristonin äskettäin foorumille (Lalli & Erik,sivu 121) oheis- tamaa Simo Parpolan esitystä uralilaisen kielikunnan ja sumerin sukulaisuudesta. (“Sumerian: A Uralic Language.” – Simo Parpola)

Parpolan esitys on menetelmällisiltä lähtökohdiltaan erinomainen.Hän on tähän men- possiblenessä löytänyt yli 1700 sanaa ja morfeemia joilla on ural-altailainen vastine. Vain pienellä osalla (7 %) on altailainen vastine,mikä onkin oikein, koska nykytietä-myksen perusteella altailaiset kielet eivät muodosta yhteistä kielikuntaa. Turkkilaisia osumia sen sijaan on paljon,ja näillä puolestaan on usein vastine myös uralilaisella puolella.Altai-laisen typologian kielistä turkkilainen on vanhastaan ollut läntisin, joten on odotuksenmukaista, että sumerilla olisi yhtäläisyyksiä juuri sen kanssa.

Isolla joukolla uralilaisia sanoja vastine rajoittuu Parpolan mukaan itämerensuo-meen. Näiden levikki siis vastaa arkaaista luoteisindoeurooppalaista lainasanaker-rostumaa, jossa myös on monia tällaisen levikin omaavia sanoja; tämä kerrostuma yhdistetään yleisesti nuorakeraamiseen kulttuuriin. Voi siis olla mahdollista sekin (vaikkei Parpola tätä pohdikaan), että tällaiset sanat ovat kulkeutuneet kantasuo-meen indoeurooppalaisilta, jotka ovat assimiloineet matkallaan jonkin sumerin sukui-sen kielen. Menetelmällisesti ei nimittäin voida palauttaa kantauraliin saakka sanoja, joilla on edustus vain yhdessä kielikunnan haarassa. Kyseessä lienee tästä syystä pikemminkin lainavaikutus (esi)kantasuomeen jostain muusta kielestä sen jälkeen, kun uralilainen yhteys oli jo päättynyt. Ei voi suoralta kädeltä sulkea pois sitäkään, että jokin sumerinsukuinen kieli olisi indoeurooppalaisten työntämänä ajautunut kauas pohjoiseen aina Baltiaan saakka.

1700 yhteistä sanaa on paljon, vaikka Parpola yrittääkin perustella määrän uskotta-vuutta.On muistettava,että kantauraliin voidaan rekonstruoida kriteerien tiukkuudesta riippuen sanoja maksimissaan suuruusluokassa 200–500 kappaletta. Tästä herää kyllä kysymys, miten sumeri ylipäätään olisi voinut säilyttää näin suuren joukon yhtei- siä sanoja. Yleisesti ottaenhan on niin,että mitä vanhemmasta kielentasosta on kysy- mys, sitä vähemmän sanoja siihen voidaan rekonstruoida. Uralilais-sumerilaisesta kantakielestä odottaisi siis löytyvän alle sata sanaa.

Toisaalta voidaan huomauttaa, että sumerin kirjoitetut lähteet ovat vanhimmillaan jo viidentuhannen vuoden takaa, kun taas uralilaisia kieliä on alettu kirjoittaa vasta vii- meisen tuhannen vuoden aikana.Aikaa on siis ollut peräti huikeat 4000 vuotta yhteis- ten sanojen kadota uralilaisista kielistä. Ja aiempi vasta-argumenttikin voidaan nyt kääntää myötäargumentiksi:tätä taustaa vasten on aivan luonnollista,että varhain tal-lennetulla sumerilla on paljon yhteisiä sanoja uralilaisten kielten kanssa mutta siten, että vastineilla on enää hajanainen ja suppea levikki nykyisissä uralilaisissa kielissä: yhdelle sanalle löytyy vastine vain itämerensuomesta, toiselle vain mordvasta ja kolmannelle vain mansista. Sana olisi siis ehtinyt kadota monesta uralilaisesta kielihaarasta - ehkäpä uudempien lainasanojen tieltä: onhan indoeurooppalaisten lainasanojen tulva useisiin uralilaisiin kielihaaroihin ollut jatkuva.

Uralilaisen äännehistorian kohdalla ilmenee kuitenkin eräitä ongelmakohtia. Parpola esimerkiksi puhuu kantasanasta *ajkwo ’aivot; päälaki’,josta sekä suomen aivot että aikoa olisivat peräisin. Kriittinen äännehistoriallinen tutkimus ei kuitenkaan tunne täl- laista sanaa. Kantauraliin voidaan nimittäin rekonstruoida sanat *ojwa ’pää, (mäen) laki’ ja *ajŋi ’aivot’, mutta näillä ei näyttäisi olevan mitään tekemistä keskenään. Mi-tään kantasanaa *ajkwo, jolla olisi näiden molempien merkitys,ei näyttäisi koskaan olleenkaan. Kantauralissa ei myöskään oleteta olleen labiovelaaria *kw - ainoa pe-ruste sen rekonstruoimiselle on Parpolalla sanueiden aivo-~ aiko- etymologinen yh-distäminen.Koska tämän yhdistämisen ainoa peruste on labiovelaarin rekonstruoimi- nen (merkityksien yhdistäminen tuntuu kaukaa haetulta),on kyseessä kehäpäätelmä.

Parpola rekonstruoi kantauraliin myös sanan *kwarüks ’varis’, mutta sananalkuisen *kw:n rekonstruoimiselle ei nytkään näyttäisi olevan mitään tukea – paitsi sumerin edustus. Tässä onkin jo ikävästi kehäpäätelmän makua: Parpola ilmeisesti pitää uralilais-sumerilaista sukulaisuutta jo niin selviönä, että hän käyttää sumerin sanojen piirteitä todisteena uralilaisen sanan rekonstruoimisessa. Tämä on luonnollisestikin metodisesti kestämätöntä.

Uralilaiselta puolelta hän esittää labiovelaarin perusteluksi tässä sanassa samojedi-kielten edustuksen, joka kuitenkaan ei välttämättä edellytä mitään labiovelaaria - sel- laista ei kantasamojediinkaan rekonstruoida. Ja vaikka rekonstruoitaisiinkin, sitä ei voitaisi palauttaa kantauraliin, ellei löytyisi sellaista sanaa,jossa olisi labiovelaariin viittaavaa vaihtelua eri kielihaarojen välillä. Lisäksi kantauralissa ei esiintynyt *ü:tä jälkitavuissa.

Sana varus on vain itämerensuomalainen, ja SSA pitää sitä vara-sanan johdoksena, mikä merkityksen perusteellakin tuntuu uskottavalta. Parpolan rekonstruktio *kwaruks siis tuskin on oikein, etenkään kun *u:takaan ei ollut jälkitavuissa kanta-uralissa, mutta toki sentään jo kantasuomessa, johon sanue voitaisiin palauttaa.

On silti huomautettava, että Parpolan rinnastukset eivät kuitenkaan ole välttämättä vääriä. Nimittäin vaihtelu sumerin g/k ~ uralin v/w voi kaikesta huolimatta olla vanha ja todellinen.Jos se on vanhaa yhteistä perintöä,voidaan uralilais-sumerilaiseen kan- takieleen rekonstruoida yksinkertaisesti *g, *w, *q (tai Parpolan tapaan *kw), ja jos se on vanhaa lainavaikutusta suuntaan tai toiseen, kyseessä on äännesubstituutio: joko sumerin g on substituoitu uralin *w:llä tai päinvastoin.

Äännevastaavuden uskottavuutta lisää muutama äänteellisestikin uskottava ja se- manttisesti yksi-yksinen sanarinnastus: sum. gíd- ’vetää’ ~ ural. *vetä- (oik. *weta-) ’vetää’ | sum. kur ’vuori’ ~ ural. *vor (oik.*woxri). Mikä tärkeintä,Parpolan mukaan sumerin š vastaa säännöllisesti itämerensuomen h:ta – kun kantasuomessa tiedetään tapahtuneen muutos *š > *h, olisikin perin vahva todiste sanojen yhteistä alkuperää vastaan, jos näin ei olisi.

Mielenkiintoinen mutta ongelmallinen ryhmä ovat homonyymiset sanat, eli sellaiset, jotka ovat (lähes) samannäköisiä ja joilla on kaksi eri merkitystä – ja vieläpä samat sumerissa ja uralissa. Tällaisia ovat Parpolan mukaan sumerin aj ’vesi’ ja aja ’isä’ ~ uralin *jäj ’jää’ ja *äijä ’isä’. Tämä olisi vahva todiste, elleivät Parpolan uralilaiset rekonstruktiot olisi omatekoisia ja poikkeaisi toisinaan hyvinkin paljon kriittisen äännehistorian hyväksymistä rekonstruktioista.

Esityksen heikoin kohta ainakin uralistin näkökulmasta ovatkin siinä käytetyt uralilai- set rekonstruktiot, joille ei aina löydy perusteita uralilaiselta puolelta. Koska näissä ”uralilaisissa” rekonstruktioissa on nojauduttu myös sumerin äänneasuun, kyseessä ovatkin oikeastaan oletetun uralilais-sumerilaisen kantakielen rekonstruktiot. Sekaannuksen välttämiseksi olisikin parempi ensisijassa verrata keskenään kriittisen tutkimuksen hyväksymiä kantauralin rekonstruktioita ja sumerin sanoja, ja vasta tois-sijaisesti esittää näille yhteinen rekonstruktio, esim.: sum. gíd- ’vetää’ ~ ural. *vetä- (oik. *weta-) ’vetää’ < S-U *kweta- ’vetää’.

On korostettava, että tämä esitys poikkeaa selvästi edukseen aiemmista yrittäjistä. Esimerkiksi kielitieteestä mitään tietämättömän lääkäri Panu Hakolan rinnastuksissa sääntönä on, että rinnastettavat sanat ovat nykytasolla samannäköisiä, mutta oletet- tujen vastineiden merkityserot ovat suuria ja merkityksenkehittymät pitkiä ja epäuskottavia (ks. http://mv.helsinki.fi/home/jphakkin/Hakola.html ).

Sen sijaan Parpolan työssä asia on päinvastoin: sanat eivät muistuta äänteellisesti toisiaan, mutta merkitykset ovat identtisiä tai hyvin läheisiä. Juuri näin pitää ollakin – ajatellaanpa vaikka suomen ja unkarin sanoja viisi ja öt ’5’, jotka ovat etymologisesti saman kantauralin sanan edustajia, vaikka niissä ei ole yhtään samaa äännettä.

Parpolan pohdiskelut sumerilaisten alkuperäisestä puhuma-alueesta Mustanmeren–Kaukasuksen ympäristössä (Majkopin kulttuuri), ovat myös uskottavia, olettaen että vertailu on kielitieteellisesti hyväksyttävissä: tällä alueella yhteys uralilaisiin ja indo-eurooppalaisiin oli mahdollinen, täältä on suuntautunut vaikutusta sumerien tunne-tulle asuinalueelle ja täältä lähtien jouduttiin ohittamaan kartvelilaisen kielikunnan alue, josta mukaan olisi tarttunut ergatiivisuus ja muita ”vieraita” piirteitä.

Sumerin eron uralilaisesta yhteydestä Parpola ajoittaa vuoden 3500 eaa. jälkeiseksi johtuen teknologista tasoa kuvaavista sanoista (valjaat, pyörä), mikä voi perinteisiin tai ”vallankumouksellisiin” jääkautisiin ajoituksiin tottuneista tuntua liian myöhäiseltä. Kuitenkin viime aikoina on esitetty perusteltuja näkemyksiä,joiden mukaan kantaura- lin hajoaminen voisi olla niinkin myöhäinen tapahtuma kuin 2000 eaa. Näihin uusiin ajoituksiin Parpolan skenaario sopiikin erinomaisesti: sumeri olisi siis eronnut kieli-yhteydestä ennen kantauralin myöhäisvaihetta ja ehkä myös jopa ennen kantauralin indoeurooppalaisia lainasanoja.

Aihe on ilman muuta jatkotutkimisen arvoinen:tässä saatetaan oikeastikin olla uuden, merkittävän löydön kynnyksellä. (Tosin muistutan,että tämä kirjoitukseni on raapaistu kasaan tunnissa, joten pidätän oikeuden muuttaa myöhemmin mieltäni, mikäli perusteltuja syitä tulee ilmi.)

Jaska

SB:Olen ottanut tässä vapauden linkittää KOTUSin etymologioita Jaskan tekstiin. Se EI tarkoita,että minä kannattaisin niitä kaikkia,esimerkiksi että vara olisi "germaania": se on vasarakirvestä, ja esiintyy myös muodossa "tavara" (joka sekin tulee *kwer- juuresta)., liettua tvara, venäjän tovar

Risto Juhani Koivula kommentoi_ 23. heinäkuu 2016 13:47

Riippumatta unkarin ja kampakeraamikkojen kielien mahdollisista sumerisuhteista Parpola iskee mielestäni tuossa vuoden 2007 avauksessaan pahasti kiveen ja pyö-rittelee päivänselvästi indoeurooppalaisia sanoja "kantasumeriuralin" sanoina. Kis-koa / gid ja vetää (ja venyä) sattavat tulla samasta *kwensti (*kweta) -tyyppisestä sa-nas- ta, varis ja korppi saattavat tulla *kwarps-tyyppisestä sanasta, korkea ja vuori/ vaara saattavat tulla samasta *kwar(k)-sanasta, aivot, aikoa ja vielä AIKA ja OIKO-Akin voivat tulla vasarakirveskielisestä *aikwo-sanasta, ja lisää löytyy, kuten myös aivan varmoja tuollaisia samanlaisia pareja. Ne todistavat itäbalttilaisesta vasa-rakirveskielestä, joka Suomessa teki kaksikin symbioosia kampakeraamikkojen SU-kielen (muinaisunkarin?) kanssa: suomen ja saamen.

Risto Juhani Koivula kommentoi_ 27. heinäkuu 2016 10:04

Tämä on vanhentunut sivu kantaindoeuroopasta, mutta antaa osviittaa...

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:List_of_Proto-Indo-European...

" *gʷer-

| |

mount |

Russ. гора (gora), Lith. guras, Skr. गिरि (giri), Av. gairi, Gk. δειράς (deiras), Alb. gur, Arm. լեառն (leaṙn), Polish góra, OCS gora "

|

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Appendix:List_of_Proto-Indo-European...

*kʷel- to turn

wheel

Ancient Greek πόλος (pólos),πέλομαι (pélomai), πέλω (pélō),κύκλος (kúklos); Latin colō; Tocharian A kukäl; Tocharian B kokale; Sanskritचक्र (cakrá); Rus-sian колесо́ (kolesó); Old English hwēol; English wheel; Old Persian (čarka); Persian چر (čarx); Old Irish cul,búachaill; Old Prussian kelan; Ossetian цалх (calx);Polish koło;Avestan (čaxra),(čaraiti);Albanian sjell;Old Norse hjól, hvel; Lithuanian kẽlias, kãklas; Luwian (kaluti-); Welsh ymochel, dymchwel, bochel

***

Viktor Orban todella sitä mieltä, että unkari ei olisi SU-kieli?

ORBAN IN HIS MADNESS HAS CLAIMED; THAT HUNGARIANS ARE DESCENDED FROM TURKS (!!!) AND DO NOT HAVE FINNO-UGRI ROOTS!

HELLO!!!??

HOW FAR CAN THE HUNGARIANS TAKE??

IN THE ESTONIAN-HUNGARIAN LANGUAGES, WE FOUND ABOUT 400 SAME WORDS WITH ALLAINGA AND OUR HUNGARIAN SÖBRA SZABO WHO LIVES IN SWEDEN

HOWEVER ORBAN TRYES, THE HUNGARIANS ARE A FINNO-UGRI PEOPLE AND SOME IDIOTS BECAME TURKS MUCH LATER!

In Hungarian, the dialectal differences are not great. It is assumed that fracture lines were already present before settling in the country, but for the nomadic people, they were not related to the place, but characteristic of the tribes. After reaching the present-day settlement, when the way of life became settled, tribal dialects developed into territorial dialects. However, due to historical conditions, sharp dialectal boundaries and large dialectal differences did not develop. However, eight dialects are traditionally distinguished, the main differences being in vocalism:

ORBAN IN HIS MADNESS HAS CLAIMED; THAT HUNGARIANS ARE DESCENDED FROM TURKS (!!!) AND DO NOT HAVE FINNO-UGRI ROOTS!??

HELLO!!!??

HOW FAR CAN THE HUNGARIANS TAKE??

IN THE ESTONIAN-HUNGARIAN LANGUAGES, WE FOUND CA 400 WORDS WITH THE SAME ROOT WITH ALLAN AND OUR HUNGARIAN FRIEND SZABO WHO LIVES IN SWEDEN

HOWEVER ORBAN TRYES, THE HUNGARIANS ARE A FINNO-UGRI PEOPLE AND SOME IDIOTS BECAME TURKS MUCH LATER!

In Hungarian, the dialectal differences are not great. It is assumed that fracture lines were already present before settling in the country, but for the nomadic people, they were not related to the place, but characteristic of the tribes. After reaching the present-day settlement, when the way of life became settled, tribal dialects developed into territorial dialects. However, due to historical conditions, sharp dialectal boundaries and large dialectal differences did not develop. However, eight dialects are traditionally distinguished, the main differences being in vocalism:

Ungari keeles pole murdelised erinevused suured. Oletatakse, et murdejooni esines juba enne maale asumist, kuid rändrahval polnud need kohaga seotud, vaid hõimudele iseloomulikud. Tänapäevasele asualale jõudmise järel, kui eluviis paikseks muutus, kujunesid hõimumurretest territoriaalsed murded. Ajalooliste tingimuste tõttu ei kujunenud aga teravaid murdepiire ega suuri murdeerinevusi. Traditsiooniliselt eristatakse siiski kaheksat murdeala, mille peamised erinevused on vokalismis:

Ungari keeles pole murdelised erinevused suured. Oletatakse, et murdejooni esines juba enne maale asumist, kuid rändrahval polnud need kohaga seotud, vaid hõimudele iseloomulikud. Tänapäevasele asualale jõudmise järel, kui eluviis paikseks muutus, kujunesid hõimumurretest territoriaalsed murded. Ajalooliste tingimuste tõttu ei kujunenud aga teravaid murdepiire ega suuri murdeerinevusi. Traditsiooniliselt eristatakse siiski kaheksat murdeala, mille peamised erinevused on vokalismis:

1) läänemurre, 2) doonautagune, 3) lõunamurre, 4) tissa, 5) palootsi, 6) kirdemurre, 7) tasandiku murre,  seekeli murre. Tänapäeval on ungari keeles murdeerinevused taandumas.

seekeli murre. Tänapäeval on ungari keeles murdeerinevused taandumas.

ad – andma

aggódik 'muretsema' – hanguma (ebakindel)

agy – aju

alá, alatt – alla, all

ár 'hind', áru 'kaup' – aru, arv, arvama (indoiraani laen)

aszó 'org, madal ala, jõgi, oja' – aas (ebakindel)

csomó – sõlm

csorog 'tilkuma, voolama' – soru 'ebakindel'

egy – üks (ebakindel)

éj – öö

él – elama

elő- 'esi-', el 'ära', elé 'ette' – esi, ees, ette

eme 'emasloom; emis', ember 'inimene' – ema

emlő 'rind, nisa', emik vanaungari 'imema' – imema

ének 'laul' – hääl (ebakindel)

és 'ja' – ise (ebakindel)

év 'aasta' – iga, iial, ikka

ez 'see', ide 'siia', így 'nii', ily 'niisugune', itt 'siin' – et, emb- (ebakindel), iga (ebakindel)

fa – puu

falat – pala (tükk)

fészek – pesa

gyakori 'sage' – jõuk

gyalog 'jalgsi' – jalg

hagy 'jätma; laskma, lubama; järele või alles jätma; pärandama; (kellegi) hoolde jätma' – kaduma

hal – kala

háló 'võrk' – kale 'paadi järel veetav võrkkott' (ebakindel)

ház 'maja' – kodu, koda

így – nii

íny 'ige; suulagi; maitse' – ige (ebakindel)

is 'ka' – ise (ebakindel)

iz, isz murdes 'igemehaigus; vähk' – ise (ebakindel)

iszik – jooma

ívik 'kudema' – jooksma (ebakindel)

íz 'liige' – jäse (ebakindel)

izé – asi (ebakindel)

játszik 'mängima', játék 'mäng' – jutt, ütlema (ebakindel)

jég – jää

jel 'märk', jegy 'märk' – jälg (ebakindel)

jó (kohanimedes) – jõgi

jut – juhtuma

kér (paluma, küsima) – kerjama

két, kettő – kaks

ki – kes

kő, köv- – kivi

könyök – küünarnukk

lel – leidma

lök – lükkama

megy/menni – minema

meny – minia

méreg – mürk

méz – mesi

mi – mis

mos – mõskma (pesema)

-nek, -nak '-le' – nemad (ebakindel)

név – nimi

néz – näge-

nyíl – nool

nő – naine

old 'lahti siduma' – avama

orvos 'arst' – arp (ebakindel)

öv – vöö, rihm

ős 'esiisa; ürgne', vanaungari 'isa; vanaisa' – isa

savanyú – hapu (ebakindel)

-ség, -ság '-us' – hing (ebakindel)

sovány 'kõhn, sale; lahja; vilets, kehv' – hubane

szarv – sarv

szem – silm

szív – süda

tél – talv

tesz/tenni – tegema

tud – teadma, tundma

tő – tüvi

új – uus

vaj – või

vér – veri

visz – viima

vő – väimees

Käsi = Kéz

veri = vér

***

Kommentit